“What I hope this book now will leave behind: the idea that new patterns like spirals or explosions or vortex streets might open our eyes to other natural shapes underlying our stories, might let us step away from the arc sometimes, slip under or through that powerful wave, glorious as it can be. I hope that other patterns might help us imagine new ways to make our narratives vital and true, keep making our novels novel.”

Jane Alison, Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative, Catapult, 2018, pages 248-9.

Think of a snowflake forming around a molecule of water clinging to a tiny particle of something, how it blossoms and diverges as other molecules join in, seeking their hexagonal destiny, becoming a perfect thing of beauty. Then think of it melting, its sharp edges blurring, its interstices blotting out until it plops to earth. That’s a story, right there, in full surround. Matter, space and time at play.

The last two sentences in Jane Alison’s brief book, quoted above, hint at a broader range of spatial patterns that authors she discusses have deployed in fiction. She sees fractals, meanders, networks and other geometric structures as literary armatures that can supplant or coexist with the conventional Aristotelian beginning-middle-end story arc.

Ever since its publication, I’ve considered starting a sequel to my novel Turkey Shoot but felt stymied because no plot seemed to gel. I had what could be its central protagonist and vague ideas about her situation, but no idea what ought to happen, or even a location or time frame for the story. Perhaps, I thought upon reading Alison’s approach to story craft, I should think different. Meander, Spiral, Explode might help me wend my way around my writer’s block.

But how to build spatial metaphors into my nascent novel in an organic way, not as literary gimmicks? They could, I hoped, serve as scaffolding for expressing themes across different locals, scenes, characters, and subplots, on which to build a narrative structure in the fullness of space-time. Embracing spatial metaphors and analogs might prevent me from rolling out a story like a reel of audiotape.

A tape player (remember them?) has two rotating reels, one full and one empty to begin with. In between them sits a component called a “head” that “reads” electrical patterns on the tape as it is drawn at a steady pace by the “take-up” reel, just as we read by flipping pages of a book from one side to the other.

Sounds and images on tape unwind. Wound up, a tape forms a spiral and a book a stack whose narrative generally obeys Aristotle’s poetics but doesn’t need to. You can lose yourself in a book or a tape, but should you skip around in it you may get lost and fragment the experience. But instead of static tape heads, suppose readers were higher-dimensional beings able to leap along the spiral or radially to other tracks. In fact, many novels take readers back and forth through time space. You can think of a work of music or literature as a matrix of content that only seems to move and change because you navigate sequentially through it. Be it a story or a symphony, its creator ought to contrive that experience by elaborating themes with an architecture that gives delight.

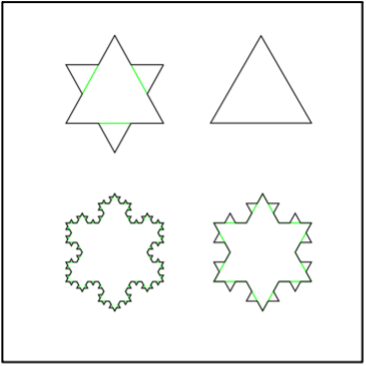

Any of the structures that Alison cribs from geometry—she explores waves, wavelets, meanders, spirals, explosions, networks, fractals, and tsunamis—can be metaphorically deployed as literary devices in a novel or even a short story, probably in poetry too. Take snowflakes, which are both “explosions” and “fractals,” forms that authors whose prose she deconstructs seem to have analogized in narratives. Explosions, such as events from which many consequences radiate, are not uncommon. Fractals are harder to write and recognize in prose. Mathematical fractals[1] are “self-similar” objects generated from a seed that replicates into a mosaic-like pattern through time and space and across scales; as you zoom in or out, you see more of the same thing in every nook and cranny.

Fractals aren’t just equations. Forces of nature spontaneously generate all sorts of them. True to themselves, snails and sunflowers spiral, rivers and trees branch, coastlines and mud flats crinkle. But how many works of literature manifest such holistic qualities beyond displaying a consistent, self-similar style? To evoke them in writing seems difficult and perhaps unnatural, but it’s possible. Jane Alison believes David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas is somewhat fractal; she also sees in it a tsunami. It’s a set of stories structured with palindromic symmetry—12345654321: “six long stories, one nested in the next” that “run from the 1850s into a shattered far future, and each story features someone who is weak and others who are monstrously powerful.” The first five are revisited in reverse order following the central futuristic one, “the only one told whole.” But each of its “cells,” she writes, “has its own texture and colors, and each makes the same sort of moves.”

Turkey Shoot has few fractal qualities. But that doesn’t mean that a sequel need follow suit. It could ramify like a Koch snowflake, successively elaborating a simple shape to generate more intricate narrative detail. For example, consider a multigenerational family saga in which each cohort recapitulates or elaborates stories of those who have gone before.

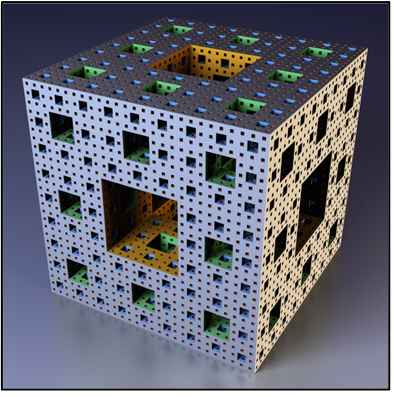

Or, like a Menger Sponge, a narrative could hollow out a prism of space-time with similar adjacent incidents, densifying until they almost merge. Think how an edict issuing from an outside power, say a central bank demanding austerity measures, can erode a nation-state. Its central bank is hit first, successively afflicting provinces, cities and then neighborhoods, families, and individuals. What was writ large comes home to roost.

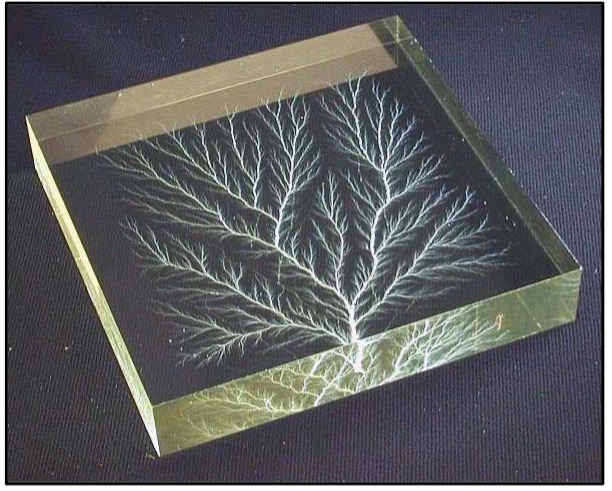

Draining static electricity from the base of an acrylic block sculpted this lacy fractal. These Lichtenberg figures branch just as trees, rivers, and blood vessels do to efficiently convey nutrients. Now consider nutrients as thoughts from different origins converging into ideas, or utterances meeting to form conversations. They continue to merge with others, building larger and larger narratives. Interactions at branching points are one-way or two-way dialogs between partners, friends, strangers, or enemies that can be friendly, casual, formal, or heated. Imagine an account of a horde of cops busting a street demonstration, each seizing a protester, corralling them in small groups that they hustle into a paddy wagon that drops them at a holding pen to join other captured protesters. That’s just how rivers channel precipitation.

I don’t know if I’ll pull off that novel or not, but I’m more likely to try having read Meander, Spiral, Explode. If you’ve been struggling to write a story, collection, or novel, pick up a copy and see where its patterns take your imagination.

Read how Geoffrey Dutton’s eventual novel used spatial metaphors in his companion essay, “Did I Tell a Fractal,” forthcoming here on bookscover2cover.com. Also read excerpts from Geoffrey Dutton’s novel Her Own Devices at The Write Launch.

[1] My fascination with fractals originated nearly 40 years ago as a developer of digital cartographic techniques. Reading Benoit Mandelbrot’s book The Fractal Geometry of Nature inspired me to code algorithms that added self-similar detail to features on digital maps, and culminated in developing a fractal global grid of nested triangles in place of lines of latitude and longitude that simplified changing a map’s scale. Code can be made to do anything but writing a fractal that isn’t an equation is much more daunting for me than programming one.