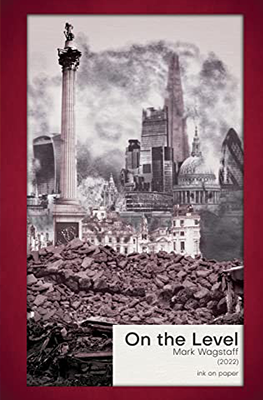

Mark Wagstaff’s new novel, On the Level, crashes the Jason Bourne films into Catcher in the Rye. Non-stop intrigue drives a coming-of-age story in which protagonist Riz Montgomery is both an unforgettably troubled, smart, and passionate fifteen-year-old and a seasoned, mysterious older woman narrating from a distant place scented by tequila and motorcycle fuel. Women, in fact, mastermind almost all the plot’s greatest intrigues, plunging readers into worlds of arms-dealers and art and a society verging on cataclysm. A final, cliff-hanging sentence propels Riz – and the imploding plots around her – toward existential risk and exhilaration.

This fun, challenging tale comes from a master of concise imagery and truncated vernacular. Wagstaff adopts a streetwise tone that contrasts with the wacky romanticism of his Attack of the Lonely Hearts (winner of Anvil Press’ 39th annual 3-day novel-writing contest) and the exquisite, poignant adolescent yearning in his “Things Left Behind on the Moon” (The Write Launch). What’s more, we’re allowed to laugh. Amid flashes of substantial beauty, the novel sideswipes with unlikely insights. A flip comment becomes universal, as when Riz’ vicious, lonely, social-climbing mother begs her absent spouse: “The children need a Father, not a colonial presence.”

Riz opens the story tough talking from a high-end London hotel suite she occupies thanks to a booking glitch for her father’s attendance at a global banking conference. A misfit in the affluent suburban town where she was routinely beaten by older girls, Riz has unwillingly undergone electroconvulsive therapy for what are, presumably, her anxiety and bipolar condition – yet she still suffers from the self-harm she inflicts to avoid feeling insects under her skin. Nonetheless, she’s an autodidact by way of TV, pop culture, and her love affair with the works of Rothko. She hopes to go to London with her dad and attend a ten-room Rothko exhibit while he leads bigwigs in saving the financial world. Instead, her mother tags along, twisting the trip into a fake family holiday involving two precociously nasty younger siblings. Riz wants nothing more than to escape; yet the Montgomerys are monitored by high-level security surrounding the dad’s conference. Less than three pages into the story, Riz finds trouble anyway, drop-rolling under the bed of an international assassin – The Man – who occupies the hotel suite next to hers. Someone left the connecting door unlocked. Riz opened it into a universe of conspiracy and betrayals, many of them hers.

The wildness accelerates from there. Riz encounters hotel security command’s fine-boned Detective Chief Inspector, Salwa Abaid – then, fearful that Salwa is trailing her, escapes to the Rothko exhibit, where she falls on her knees before Black on Gray. There, Riz pauses for one of Wagstaff’s characteristic doses of gorgeous. He pulls us into caring about this difficult, reckless adolescent who, in a nod to Tracey Emin, describes the exhibit: “Everything beautiful the big way, the way a girl’s unmade bed can be beautiful, when it carries the care and forgiveness of people who’ve needed her or been needed. Art is that or nothing.”

When Riz protests a tourist guide’s calling Black on Gray “empty,” who shows up but The Man, lethally dapper and holding a museum catalogue while quoting Stanley Kunitz’ eulogy of Rothko. Paying her more attention than her father ever did, The Man purportedly makes amends for the drop-rolling incident by taking Riz out for espresso in an unforgiving Italian café. She observes: “He didn’t dress to own the joint. He dressed to eat whoever owned the joint.”

As she will be many times in the story, Riz is humiliated by her presentation as a heavy-set, awkward, terrified child amid suave and dangerous adults or lean and shining boys and girls who remain out of reach. The bizarre father figure that is The Man seems to understand Riz and possibly to care about her eventually – though, having no child of his own, he doesn’t treat her like one. He will come to perceive her eerie intelligence and that she’s been bullied, let her fight to the edge before he saves her from a knife-wielding gang, honor her developing moxie, all while acknowledging that Rothko is about hope; yet he uses her. At the café, he pays for espresso with “mythically large” paper currency and gives her the Rothko catalogue bearing fingerprints that will become a trap. Which is why, back at the hotel, Salwa steals the catalogue straight from Riz’ fingertips.

Still to come: arms-selling Russian thugs serving their influential customer Dersima; Lilija, a dazzlingly blond, white-clad Baltic spy posing as hotel staff bearing feedback forms; Vespa chases; trans flamenco dancers; and Riz’ becoming the tough person she wants to be by consuming far too many substances, recovering from heedless injuries, and staring down the barrel of Salwa’s firearm. Early on, and perhaps most poignantly, Riz yearns to belong to a cell of young, privileged insurrectionists she meets at the bar she’s wandered into and falls in love with their leader, “Mocha” – a beautiful, ruthless young woman of mysterious heritage whose real name Riz never learns. Mocha pumps Riz for info on the banking conference and The Man and by story’s end, may or may not forgive Riz for apparently delivering Mocha’s compatriots into the hands of raiding police. The novel’s conspiratorial characters connect in byzantine ways – some of which suggest they are Riz’ surrogate family. She betrays them all by agreeing to work for each.

She snitches on them profligately because she yearns for acceptance, someone to talk to, to hold hands with, to put arms around her, to consider her relevant. Not only does she never receive phone messages from friends – she lives with the knowledge that her mother would have aborted her had the procedure not been tactically inadvisable for the career of her current husband, who is not Riz’ biological father. Despising her own tears, Riz cannot help thinking: “There were girls at my school shared clothes with their mum. They did lunch.” The simplicity of her longing is probably the most dangerous thing about her. Yet her vivid internal conflict tantalizes.

Mirroring lost teenager Holden Caulfield in Catcher in the Rye, Riz holds something inside her that is too big for her heart and most of the surrounding adults. Neither youngster can stand phoniness or the expectations of the affluent families and societies into which they were born. Each rebels toward a self-defined truth. They diverge, however, with respect to their response to the human condition.

Still mourning the death of his brother, Holden absorbs other people’s melancholy. He is capable of being torn up by the embarrassment of a poorer student whose suitcases can’t measure up to Holden’s Mark Cross; or by kids grabbing for the gold ring on a carrousel. He wants to catch children before they fall innocently off an imagined cliff. Holden’s myth is rescue.

Riz’ is self-preservation. Though she can watch young Hyde Park prostitutes and wonder if they get a coffee break, where they live, who they love, her sympathy is for the most part self- directed – perhaps because her central grief is existential: she is “unloved and unwanted.” Even now, her mother would have part of Riz’ brain surgically excised to make her more docile. Accordingly, Riz’ task is to survive. Possessed of far more substance than corrupt agents and state actors who have so little regard for the mayhem they cause, she becomes a player herself –a violent one – rather than remaining a reactive victim. She leaps off an imaginary cliff into the future, then runs toward the unknown, broader repercussions be damned. She explodes the confines of her place in society and ends up living outside the law, where she is free.

Paradoxically, there is much to love about Riz’ vulnerability, though like Holden, she is unreliable in a thousand ways – not least as a narrator. How did she know about the foregone abortion? Is her mother really as bad as she’s depicted? How is Riz always the one who’s been done dirt while objectively, she makes herself impossible and betrays multiple agreements, confidences, people?

The facts are ambiguous and so is the narrative voice. From the first pages, Spanish language references, needing a “truck of tequila” to talk about her mother, and recognizing common signals that cops are lying – insight seemingly beyond Riz’ suburban experience – call into question whether the speaker truly is a small-town British fifteen-year-old. Riz’ elder self is a recurring stealth presence – one who has retreated into arid, hard-drinking places populated by “vanilla-scented camareras.”Grown-up Riz comes at the reader obliquely, through hints of regret and diamond-hard experience. She might be living somewhere in the American Southwest or in Mexico. She emerges, then melts away. Is she on the lam? Have people just given up looking for her? One might wish Wagstaff had made his ambiguous narrator’s worlds clearer, allowing us to ponder the consequence of Riz’ choices. Instead, he operates through whiffs of fragrance and anonymous miles on the run. He invites us to investigate clues about Riz the elder and hold them in reserve while enjoying her younger self’s wild ride.

In the end, On the Level is a read that asks simultaneously for suspension of disbelief and an admission that conventional society’s underpinnings might be more as Wagstaff suggests than we’d care to consider. Riz’ risks are great, the global consequences of her involvements dire. At a personal level, the reader may ask whether she has matured by the end of this coming-of-age novel; or whether deepened awareness lies embedded in her appearances as a toughened, if nostalgic, adult. Whatever wisdom grown-up Riz has earned, it was surely not acquired through normal schooling, which “never taught her to dodge love or bullets.” Her life’s education has come through action, Mocha, Salwa, Lilija, and The Man, for whom she served as decoy the last time she saw him:

You may ask why I did what he wanted. Guess if you do it means no one made you coffee. No one told you that you make sense. No one stood beside you in awe of Rothko. What choice did I have? He was my neighbour.

Does the adult Riz, wherever she is, still love Rothko, by the way? One senses the answer is: More than ever.

Read also Mark Wagstaff’s essay “Making It Up.”