I’ve never seen a dead horse in person. I read a poem recently that said when you see a living horse you’re supposed to yell out horse! and if you don’t it’s a sign of a sociopathic mind of some kind or other.

Thus begins a story titled “They have the largest eyes” in this collection of “fictions” by Luke O’Neil called A Creature Wanting Form that features animals large and small, perhaps the least interesting of which are Homo sapiens. At least what most of them do is pretty uninteresting, and that’s one of his points. The other animals involved, ranging from ant to whale, have more stage presence, even those that are dead.

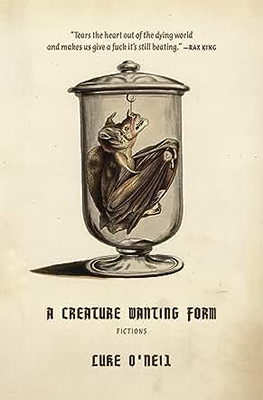

In fact, betwixt stories the book provides a bestiary of assorted critters, thirty or so 18th and 19th century drawings and etchings, for you to contemplate. Except for the bat-in-a-bottle on the front cover, they aren’t creepy, just odd. As are the story titles, which tend to be oblique.

You could say that about the author, too. Odd in that he’s frequently transfixed by thoughts of mortality, his and others’. Even though they’re billed as “fictions,” many of these little gems feel deeply personal, whether written in first person or not. ”You can’t take it with you,” one of the longer ones (10 pages), is a good example. In it we read:

I think the idea of all this living is to accumulate enough loving and having been loved experience points that you can cash them in in one fell swoop at the end for an ameliorating effect on the descent but the prospect of that never brings me any comfort because it’s all erased on the other side of it anyway. A new ledger in which your balance isn’t zero it’s nothing. I guess there isn’t even a ledger anymore anyway.

People say you can’t take your money with you when you die but you can’t take your love with you either. (p. 187)

As you can sense, there’s an inescapable life-and-death motif running through the chapters. Some are less than a page long. Most are from one to five pages and can be read in a couple of minutes.

But that’s only if you’re not paying much attention to what O’Neil is saying and how he says it. If you are, you will find unique descriptions, well-chosen verbs, literary allusions, odd interactions, and meandering ideas that give pause. As O’Neil’s sentences tend to be long and always omit commas (which his magazine editors tended to put back in), his prose takes more time to scan than one may normally be used to. The lack of quote marks in dialog also makes for slower going, but that’s okay because you’re hooked.

“They have the largest eyes” is written in first person. He’s watching TV, which occasions what seems to be an irrelevant digression about cops in Hawaii that ends with a faint connection to the main topic, horses:

There are no horses or many land mammals of any kind on Hawaii originally they all had to be brought there by people on boats.

At this point a second person is introduced in a long sentence without any breaks, followed by an existential punchline:

Years ago I told you I liked to look at pictures of horses fighting sometimes and you thought that was a weird thing to do and I said it had never occurred to me as long as I had lived for some reason that horses would fight each other but once I knew that they do it made me look at things differently. Horses mainly but also everything. (p. 148)

After that things get dark. While this piece is something of a downer, you shouldn’t pass it by.

That’s the thing with Luke O’Neil; you are typically clueless about how things are going to go but are pulled by the tide of his narrative. And speaking of tides, a disproportionate number of these stories take place within spitting distance of the ocean. (The Atlantic, along Boston’s South Shore or Downeast.) There’s a story in which people congregate to watch a pink beach house get swept up into the sea (“Newburyport Massachusetts,” p. 80) that goes on to speak of hermit crab battles and people falling from airplanes and ends with a line from Walt Whitman. That sort of shit, as O’Neil might say without that comma.

While it would be stupid and possibly insulting to emulate O’Neil’s unique style, it does provide some interesting rubrics. He inserts a lot of vaguely trite vernacular, like “some kind or other” (above), “one way or another” (p. 55), “for as far as it went” (p. 81), “by any stretch of the imagination” (p. 34), or “I don’t know man I don’t know how you say that sort of thing.” (p. 69).

Another trick up his sleeve is to affect a detached perspective, even in first or second person, that gets to you:

Maybe the world is ending or maybe you have an idea it is going to soon and someone tells you that you could get on a ship and while there is no guarantee what will happen you have a very good chance of reaching another Earth-like planet. Of getting out and walking around for who knows how long. Maybe the rest of your natural life.

Then again maybe you’ll be snatched from the ground by a space pterodactyl and hoisted up into the sky screaming. (Kingston Street, p. 82)

It somehow calls to my mind the sort of aseptic language found in NOAA weather reports minus commas:

A chance of showers before 9am, then a chance of showers and thunderstorms between 9am and 1pm, then showers likely and possibly a thunderstorm after 1pm. Partly sunny, with a high near 88. Southwest wind 5 to 10 mph. Chance of precipitation is 70%. New rainfall amounts between a quarter and half of an inch possible. (Forecast for July 29, 2023 in our area.)

While Creatures relates few triumphs of the human spirit, I don’t mean to imply that the whole book reads as nature’s revenge served cold. Some stories ping-pong you just for the hell of it. The last story, “I want to see you dance again” (p.256, at a record 18 pages long), starts with a guy looking at a video of a talking crow when his wife wants to talk about a moth infestation. It loops around without much fear and loathing (other than for insects) en route, and comes around full circle to considering how birds can talk, apropos of nothing else in the story. Because if its episodic, disjointed nature and unquoted dialog, some of which might be the narrator (who sometimes goes into first person and then back to third) narrating, I had to read it twice and still don’t know its bottom line. Here’s a discursive, slightly autofictional, excerpt from it; the woman is speaking:

I don’t love [spiders] either but more so I don’t like it when I see twenty of something. When they’re really good at producing eggs and multiplying that makes me crazy.

Did you see Heidi Klum’s costume?

Why? Oh because of the theme we’re working inside of.

Yeah.

Well she…

I don’t love it but it’s more than just funny. How do you spell Scarlet Johanson?

Scarlett Johannson. Two t’s two s’s.

So afterwards she took off the worm body and… (p. 265)

See what I mean? And that’s not the only pointless digression.[1] Well, maybe there’s a point to them but it’s not always easy to get it. O’Neil’s approach to storytelling reminds me of radio raconteur Jean Shepard (possibly before your time, so here he is on Letterman). Shep’s stories—often about his boyhood, relatives, or days in the Army—could take an hour to unreel, and just when you think he’s lost it, he finishes up with whatever topic he started with. And he did this six nights a week on WOR AM for years without scripts.

But I digress. O’Neil’s stories somehow capture and illuminate our world slouching toward oblivion as we amuse ourselves with trivia, gossip, and videos, and all of them seem to come straightaway from his experience. Or at least from vicarious ones that he ingests, like the video of a talking crow telling its owner, “Hi Jim. The Hangman is coming.” Yep. And when he comes, I’m sure O’Neil will invite him in and tell him stories.

You won’t find an author bio in the book or on his bottomless website, but his publisher has posted:

Luke O’Neil is the author of the popular political and literary newsletter Welcome to Hell World and the book of the same name. He’s a former writer-at-large for Esquire and longtime contributor to the Boston Globe, The Guardian, and many other newspapers and magazines.

[1] Here’s another one in its entirety:

A truck was groaning outside and there was a thud on the stoop.

Did you order something he asked.

Yes she said.

What did you order?

Nothing she said.

That’s the end of it. Shoots right by.