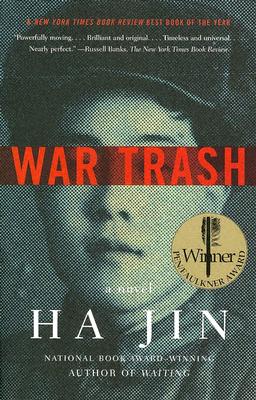

As I was lying on the acupuncturist table, letting the needles do their magic, I listened to the music playing quietly in the room. My acupuncturist is from Korea and the music he plays is Korean. Suddenly, I realized that what I was listening to could be what the main character listens to in Ha Jin’s War Trash. As I listened to the music, I imagined the characters making their beloved musical instruments out of scraps of wood, discarded pipes, pieces of rope woven into strings, metal barrels cut in half and molded into shape. I felt the presence of Yu Yuan, “a scholarly and self-effacing clerical officer in Mao’s ‘volunteer’ army” who was taken prisoner south of the Thirty-eighth Parallel during the Korean War, listening to the music played by his fellow captured soldiers. Then I realized that a novel can linger in the background of my life, that maybe I don’t quite realize the effect a novel has until I encounter something in my environment that corresponds or relates to a theme or a main character’s journey.

War Trash isn’t my favorite novel. Ha Jin isn’t my favorite writer. But the novel is important for me because it shows me a part of history I didn’t know. (Ha Jin wrote a fictional novel, but the detail and events are factual, and the bibliography is extensive). I didn’t know what life was like for the Chinese and North Korean prisoners in an American prisoner of war camp. I didn’t know about the other war these men experienced inside the camp or what they faced as they were waiting to be released. Yu Yuan is an only son, his mother is alone back in China, and his young fiancée is waiting for his return from war. All Yu Yuan wants to do is to go back to his home on Mainland China and fulfill his responsibilities as a good filial son, raise a family, have a good job, and grow old with his loving wife-to-be. But there is another powerful movement within the camp between the Mao’s Red China, the ex-patriots, and the Chiang Kai-shek followers. What does Yu Yuan do? How does he decide?

I don’t want to give away what happens to our hero, Yu Yuan, by the end of the story. But I will say that reading about the Chinese prisoners—both Mao’s Red Communist idealists and the common person of the volunteer army—plus the North Koreans captured by the Americans and imprisoned in an American prisoner of war camp made me realize that war is the same, no matter when or where it begins or ends.

The title of the novel, War Trash, is telling, and a few beliefs remain the same for me—war is cruel and politics in the wrong hands is dangerous. Yet, the human spirit endures.

1 comment

what a great review–thanks for this and the way you fit so much detail and feelings into a short review. i love what you said about a novel lingering in the background of your life; so true, and thoughtful. and isn’t it a wonderful feeling when it all connects?!