Where do we come from? Creation Myths give us the answer(s).

What are we doing? Trickster Stories tell us what not to do.

Where are we going? Hero stories and legends often answer this third basic human question. Hero Stories tell us who we are by telling us whom we admire. Legends tell us what we can become. Dragon Slayer, Prophet, Rags to Riches Entrepreneur, and Great Warrior Legends tell us where we are going, as individuals and as a people.

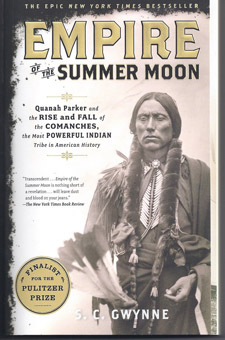

S. C. Gwynne’s Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History is an historical narrative of heroes and legends set against the panorama of the American West, particularly the Texas frontier between the years 1836 and 1912. In particular, Gwynne narrates the story of an American legend, Quanah Parker, but on a much broader measure, his eye-opening narration accurately and lyrically narrates three histories: one of the settling of the state of Texas; the second of the forty-year war against and destruction of the Indian tribe called Comanche; and the third, the saga more than the history of Cynthia Parker, who was kidnapped by Comanche as a nine-year-old girl, was integrated into the tribe, and birthed and raised the legendary Quanah Parker. Her history is a saga because she never tried to escape her Comanche life. She refused to return to “civilization” and, subsequently, had to be captured and returned to her Parker family as a prisoner.

Because Gwynne traces the course of three histories and the lives of Quanah Parker and his chief adversary, Brigadier General Randall Slidell MacKenzie, and because the history of Texas is inexorably tied to the history of the United States, Gwynne’s narrative is non-linear. This review, of necessity, occasionally reflects a few of Gwynne’s temporal juxtapositions.

Although the war with the Comanche coursed four decades, beginning with the superior horsemanship of the Comanche executing individual skirmishes and guerilla-style raids on isolated settlements during the 1830s, and ending with battalions of Civil War hardened army units and the superior firepower of Gatling guns and Sharps buffalo rifles choking off and hunting down the last remaining Comanche warriors in 1876, Gwynne begins his narrative in 1871 with the keyword “remember”: “Cavalrymen remember such moments: dust swirling behind the pack mules, regimental bugles shattering the air, horses snorting and riders’ tack creaking…. The date was October 3, 1871. Six hundred soldiers and twenty Tonkawa scouts had bivouacked on a lovely bend of the Clear Fork of the Brazos…. Though they did not know it at the time…the sounding of ‘boots and saddle’ that morning marked the beginning of the end of the Indian wars in America, of fully two hundred fifty years of bloody combat that had begun almost with the first landing of the first ship on the first fatal shore in Virginia.”

The word “remember” is key. Memories are imperfect and often manipulated to fit judgments. Memories can be the whole cloth from which legends are sewn.

Up until the end of the American Civil War, the Comanche roamed and ruled over a vast country. The east/west boundaries stretched from present day Waco, Texas, to Santa Fe, New Mexico. The northern boundaries reached into Kansas and Colorado, and the southern borders carried into northern Mexico. It was a territory as large as the present state of Texas, and the Comanche knew every stream, river, spring and canyon, bluff, cottonwood grove and hiding place in that area. It is no wonder it took forty years to subdue them.

The troops that left a bend of a fork of the Brazos River in Central Texas on October 3, 1871, were under the command of civil war hero, Randall Slidell MacKenzie, a moody, implacable, difficult, and ruthless adversary by anyone’s reckoning. MacKenzie was Sherman’s brigadier general in the scorched-earth march on Atlanta seven years previously. Quanah Parker bested Randall MacKenzie every time they skirmished; even so, Quanah Parker and Randall MacKenzie were each other’s measure. There are those in Texas who call MacKenzie a legend. If a man is measured by the strength of his enemies, it follows that it requires a legend to be the measure of a legend.

In 1871 William Tecumseh Sherman was President Grant’s Army Chief, and the exasperated President had taken off the gloves regarding the Indians on the Great Plains. They were to be “exterminated.” George Armstrong Custer was sent to subdue the tribes of the Northern Plains, and MacKenzie was dispatched to the Southern Plains to kill Comanche in particular, but also kill Kiowa, Arapahoe, Cheyenne, and any other tribe (and raiders from Mexico) who got in the way.

For MacKenzie, the Comanche were the target. No American Indian tribe in the history of the Spanish, French, Mexican, Texan, or American occupation of the Southern Great Plains had caused as much havoc, destruction, and death as had the Comanche. White settlers in eastern Texas, even in 1871 when Gwynne’s narration begins, were being pushed in terror back towards whence they came by Comanche warriors.

Although readers may be more familiar with the Apache and the Sioux, it was, in fact, the ‘legendary’ fighting ability of the Comanche that determined when the American West opened up. Comanche boys became adept at bareback riding by age six; Comanche fighting men were considered by their adversaries to be the best horsemen who ever rode. The Comanche were so masterful at war from horseback, so adept with bow and arrow and lance while at full gallop, that they stopped the drive of colonial Spain from Mexico and halted French expansion westward from Louisiana. Ironically, if the Comanche had not been so successful in repelling the Spanish and the French, America would probably not be the country it is today.

Just three days after embarking on his first foray into the heart of Comanche territory, MacKenzie met his match. Around midnight on October 6, 1871, Quanah and his warriors charged MacKenzie’s camp in Blanco Canyon and stampeded six hundred horses, stealing seventy of the best ones, including MacKenzie’s. Blanco Canyon gave MacKenzie his first look at Quanah.

A 4th Cavalry captain named Clark offered this description of Quanah “in battle on the day after the midnight stampede”:

“‘A large and powerfully built chief led the bunch, on a coal black racing pony. Leaning forward upon his mane, his heels nervously working in the animal’s side, with six-shooter poised in the air, he seemed the incarnation of savage, brutal joy. His face was smeared with black warpaint, which gave his features a satanic look…. A full-length headdress or war bonnet of eagle’s feathers, spreading out as he rode, and descending from his forehead, over head and back, to his pony’s tail, almost swept the ground. Large brass hoops were in his ears; he was naked to the waist, wearing simple leggings, moccasins and a breechclout. A necklace of beare’s claws hung about his neck…. Bells jingled as he rode at headlong speed, followed by the leading warriors, all eager to outstrip him in the race. It was Quanah, principal warchief of the Qua-ha-das.’”

This reviewer has cause to smile at the above description. This reviewer was raised on an Indian reservation and has been involved with American Indian ceremonial ways for over thirty years. I have ‘sat up’ in Native American Church ceremonies with modern day Comanche, and have attended a Parker family reunion powwow in Cache, Oklahoma, near Fort Lawton where Quanah is buried. I have spoken at length about Quanah Parker with a few of his direct descendants. Captain Clark’s lofty description adds to the legends about Quanah, but certain aspects are not likely to be true. No Indian warrior, no matter his status, ever rode into battle with a body length headdress. To do so would have been ridiculously vain and physically impractical. Even smaller, shoulder-length ‘war’ bonnets usually consisting of twenty-eight feathers, symbolizing the number of ribs in a buffalo, was impractical. Comanche warriors were renowned for their ability to hang to the sides of their horses and shoot firearms and/or arrows from under the horses’ necks. Full war bonnets or full-length ceremonial chief’s regalia would not allow this kind of horsemanship. Quanah might have had a colorful beaded bow quiver on his back, which could have confused Captain Clark. Bear claws are heavy and are either ornamental or used in healing ceremonies. Clark probably saw a bone breastplate designed to deflect arrows. It would have been egoistic of Quanah to wear bear claws, a full headdress, and brass hoops in his ears. Again, it would not be something a man would wear in a battle or even a firefight. Quanah may have worn feathers, probably no more than seven attached to a braid on one side of his head, but even so, he would have tied up not only his own hair, but also his horse’s tail. Long hair and horses’ tails can be grabbed, which in either case would tear or throw a rider from his horse. Bells jingling? The Comanche were masters at stealth. Captain Clark’s description sounds like he saw a powwow dancer, not a warrior chief.

If Clark’s account is true—if he truly did see Quanah in such regalia—it could only have been after a battle lost by the cavalry. Quanah was more than happy to taunt his enemies. He and his warriors may have appeared in full regalia riding in a circle outside rifle range. The night before, they had apparently ridden into the middle of a camp, shot a dozen men at point blank range, stampeded six hundred horses, kept seventy of the best, and left an entire regiment of cavalrymen on foot. These 4th Cavalry pony soldiers were humiliated only three days after their much-heralded Comanche hunt began. Quanah would have readily taunted them, and a memory of the event by a defeated and humiliated soldier very well would have been exaggerated to help cover the humiliation. Clearly, from such descriptions legends are made.

S. C. Gwynne’s unquestioning quoting of Captain Clark is one of the few flaws I found in this entire narration of the history of the Comanche Wars, the saga of Cynthia Ann Parker, and the legends about Quanah.

MacKenzie was ordered to fight fire with fire, to be as merciless toward the Comanche as the pitiless Comanche were toward the settlers. Yet, as ruthless as the soldiers were towards the Indians, the ultimate subjugation of all the Plains tribes was gained by exterminating the great bison herds.

In 1870 a new tanning technique made the turning of buffalo hides into high-grade leather a most profitable enterprise, and “the first large-scale slaughter of buffalo by white men with high-powered rifles took place in the years 1871 and 1872.”

The introduction of the Sharps high-powered buffalo gun added to the slaughter. Buffalo hunters and skinners swarmed onto the High Plains. During 1872 and 1873, five million bison carcasses were left to rot on the Plains. That’s an average of five thousand a day and all from the Southern Plains herd—the lifeblood of the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Arapahoe, and Southern Cheyenne. How do we know that number? The hunters only wanted the hides, and five million hides were shipped east by train from the railhead at Dodge City during those two years: “As one scout traveling from Dodge City to the Indian territory put it: ‘In 1872 we were never out of sight of the buffalo. In the following autumn, while traveling over the same district, the whole country was whitened with bleached and bleaching bones.’”

Killing the Plains Indian’s food was not just an accident of commerce; it was a calculated political act. As General Philip Sheridan put it, “ ‘They are destroying the Indians commissary…. For the sake of a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated.’” Sheridan is also memorably known for saying, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

There is no way to absolutely know how many buffalo or bison were ultimately killed. Gwynne states unequivocally: Buffalo men “would kill thirty-one million buffalo” between 1868 and 1881. Best estimates are that thirty million bison covered territory from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border and from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. In 1889 only five hundred remained on a protected range in Montana. Do the math and, mind-boggling as it may seem, an average of 4,100 bison a day were killed over the twenty-year period from 1868 to 1888.

After noting that Quanah and MacKenzie first met (without recognition of their conjoined destiny) in 1871, Gwynne’s narrative then returns to 1836 and the kidnapping of Cynthia Ann. Gwynne notes that MacKenzie must surely have known the story of the nine-year-old white girl kidnapped by a Comanche raiding party from Parker’s Fort, ninety miles southeast of Dallas. Although Comanche kidnapped many children and women, Cynthia Ann became the most famous of all the Indian captives of the era: first, because two uncles searched for her without success for a dozen years, commencing in 1841 when reports came in that she was still alive and a “captive”; and second, because when she was re-captured on December 19, 1860, by Texas Rangers and soldiers from the Second Cavalry, she tried repeatedly to escape and refused to return to her people. Subsequently, she and her baby daughter, Prairie Flower, were brought back under guard as prisoner. Her refusal challenged the most fundamental assumption by whites about Indians: Given the choice between living with “civilized” Eurocentric Christians and savage, sinful Indians, no one would ever choose the latter.

Cynthia Ann, on the other hand, forgot English, learned Comanche ways, became a full member of the tribe, married Peta Nocona, a prominent war chief, and had three children of whom Quanah was the oldest. Ironically, Charles Goodnight, who sixteen years later became an admiring friend of Quanah Parker, led The Texas Rangers who recaptured her in 1860.

The child, Prairie Flower, lived only four years after capture. Following that death, knowing that her husband was dead, and thinking that her two sons had also been killed in the battle that had led to her capture, Cynthia lapsed into severe depression. It was reported by the relatives who kept her, sometimes locked up, that she heard voices and saw ghosts. She spent hours sitting on the porch of the home of her younger brother Silas weeping or singing Comanche mourning songs. She slashed her arms with knives whenever a family member died. She attempted several escapes simply by wandering off, sometimes barefoot, and setting out across country with no supplies. She continued to practice the religious ceremonies of the Comanche and to wear tribal clothing until those clothes were threadbare.

She was also an object of immense curiosity and many newspaper accounts. She had to hide from “gawkers” who came to see the “white squaw.” There were few in Texas who did not know about her and her story, but it was after her death and not until the surrender of Quanah in 1875 that she became known as the mother of the legendary Comanche Warrior. So it was that when MacKenzie first encountered Quanah on the Brazos River in October 1871, he knew of Cynthia Ann Parker, but he did not know that the warrior who bested him was her son.

The saga of Cynthia Ann Parker has been fictionalized in novels and film, the most famous of which is The Searchers, and the most recent of which is Dances With Wolves. The curiosity about her did not, however, make her heroic or legendary in the eyes of white society; her story is an intriguing saga in Texas history, and Parker family descendants continue to be a prominent Texas family to this day.

Gwynne has this to say about her: “Who was she, in the end? A white woman by birth, yes, but also a relic of old Comancheria, of the fading empire of high grass and fat summer moons and buffalo herds that blackened the horizon. She had seen all of that death and glory. She had been a chief’s wife. She had lived free on the high infinite plains as her adopted race had in the very last place in the North American continent where anyone would ever live or run free. She had died in deep pine woods where there was no horizon, where you could see nothing at all. The woods were just a prison. As far as we know, she died without the slightest comprehension of what larger forces had conspired to take her away from her old life.

“One thinks of Cynthia Ann on the immensity of the plains, a small figure in buckskin bending to her chores by a diamond-clear stream. It is late autumn, the end of warring and buffalo hunting. Above her looms a single cottonwood tree, gone bright yellow in the season, its leaves and branches framing a deep blue sky. Maybe she lifts her head to see the children and dogs playing in the prairie grass and, beyond them, the coils of smoke rising into the gathering twilight from a hundred lodge fires. And maybe she thinks, just for a moment, that all is right in the world.”

Because she disdained civilization for life as a Comanche, her Comanche descendants from Quanah Parker regard her as a heroine, a cut-above, and a legend in the sense that she is the mother of a legend. So does, it seems, S. C. Gwynne.

Even so, open the book to sections rendering pure historical accounts and Gwynne’s prose is equally expressive and accurate: “Though Medicine Lodge was ostensibly a bargaining session, in fact there was no bargaining at all.…The Plains Indians resided in the heart of the last frontier, and their land was not simply wanted as a pass-through for trains and wagons heading west. Comanchera itself was coveted by white men. Sherman told the Indians they would have to give up their old ways and learn to become farmers. And there was nothing, they were told bluntly by the man who had overseen carnage on a scale that these Indians could not possibly comprehend, they could do about it. ‘You can no more stop this than you can stop the sun or the moon,’ [Sherman] said. ‘You must submit and do the best you can.’”

The Comanche hated the buffalo hunters above all others, and so, on May 1874, gathered two hundred fifty warriors together on a bluff overlooking the buffalo hunter’s town of Adobe Walls north of present day Amarillo. Ill-advised by a colorful but scheming “prophet,” Isa-Tai, who claimed his medicine made him impervious to bullets and who had a vision of a new order on the Plains, and Quanah, in league with Kiowa Chief Big Bow, attacked just before dawn, not knowing that jealous rivals of Quanah and Isa-Tai betrayed the secrecy of their attack. The hide men were awake and waiting and armed with .50 caliber long-range Sharps rifles capable of killing a buffalo at one thousand yards. The Indians never had a chance. In retreat, Quanah’s horse was shot out from under him at five hundred yards, and he was hit in the shoulder by a ricocheting bullet. Isa-Tai had his horse shot out from under him at one thousand yards. The following quote describes what happened next:

“Though the Indians remained nearby for the next several days, taking occasional shots at the sod walls of the trading post, they never attacked again. The battle was over. On the third day Billy Dixon made what became the most famous single shot in the history of the West. A party of about fifteen Indians had appeared at the edge of the bluff, at a distance of probably fifteen hundred yards, or almost a mile. As Dixon recalled, ‘some of the boys suggested that I try the big ‘50’ on them…. I took careful aim and pulled the trigger. We saw an Indian fall from his horse.” He was the last casualty of what would become famous in frontier history as the Second Battle of Adobe Walls….’”

Again, Gwynne’s accurate historical accounts are expressive in that his words suggest a bravado that underpins cowboy legends.

The defeat for the Comanche and Quanah at Adobe Walls was devastating, if not quite conclusive. The conclusive defeat would come four months later.

In September 1874, MacKenzie, who had learned a great deal chasing Quanah all over northern Texas, accidentally came across and annihilated a Comanche village in Palo Duro Canyon south of Amarillo. MacKenzie slaughtered fifteen hundred Comanche horses, the source of Comanche wealth and power. Quanah was not present. Had he been, his scouts would have known of MacKenzie’s presence.

Following this overwhelming loss, slowly but surely all remaining renegade Comanche surrendered to the reservation. Quanah was not the last to come in, but once under a white flag and living on a reservation, he wisely found, negotiated with, and brought in the only other band of Comanche roaming destitute but free. The following quote illustrates what the Comanche had surrendered to the “white man”:

“…in March 1878 a group of Comanche and Kiowas, including some women and children, were finally allowed to go, unsupervised, on a hunt. This was cause for great excitement among the Indians. Perhaps it was the simple urge to validate their own past, or maybe a desire to show their children who they really were. They would ride out again into the great oceanic wilderness that so terrified the taibos [settlers]. They would kill and eat, and use the gallbladder to salt the raw bloody liver, and drink the warm milk from the udders mixed with blood, and it would be, however briefly, like the old days.”

They knew the hide hunters had killed many buffalo, but what shocked them was to find the hide men had killed all the buffalo. The idea of traveling one hundred miles and seeing only bleached bones and not one single buffalo was unimaginable. Heartbroken, Quanah led the small group all the way to Palo Duro Canyon, their former stronghold and sanctuary, to another shock: “On a bitter cold day, with snow on the ground, the Indians entered the canyon…. The intruders were in an ugly mood, having just learned that their sacred canyons now ‘belonged’ to someone else.” A former Texas Ranger and now land baron and cattleman, Charles Goodnight, “owned” the Canyon.

A parley with interpreters was arranged between Goodnight and Quanah. Goodnight asked Quanah through the interpreter what his name was. Quanah replied in English with a highly symbolic answer: “Maybe so two names—Mr. Parker or Quanah.” The reply was symbolic because it indicated that Quanah had realized he could no longer deal with the world via his old cultural references. To take the name “Parker’” voluntarily was not an acceptance of defeat but recognition of the hopelessness of his tribal ways in the face of the advance of “Western Civilization.” My reading of that moment tells me that Quanah Parker was accepting the challenge and responsibility of leading the whole Comanche tribe on the difficult road into the reality of their new circumstances. The buffalo were all dead and the white men now owned the sacred canyons.

Quanah Parker made a makeshift treaty with Goodnight that day. In the years following, the two became good friends, with Goodnight leasing land from Quanah’s reservation holdings. Through his dealings with cattlemen, Quanah became a cattleman in his own right.

Even though Goodnight ate at Quanah’s table, Gwynne makes no further reference to the fact that Charles Goodnight led the band of Texas Rangers who, in 1860, killed Quanah’s father and captured his mother and sister. Apparently, Quanah never knew this fact about his rancher friend. It was General MacKenzie who, even before he met Quanah in person following Quanah’s surrender, sought and got the information for Quanah that his mother had died in 1870. MacKenzie admired Quanah. MacKenzie’s interest in Cynthia Ann and Prairie Flower began a remarkable friendship between these two legendary adversaries, which lasted until MacKenzie’s death in 1889.

Beginning in 1880, Quanah Parker’s singular negotiating skills in leading the Comanche tribe into the twentieth century earned the respect of the United States government. Such was the respect they had for him that no one objected that he maintained seven wives and their children in a spacious ranch house on the edge of Fort Sill, Oklahoma. He had his own private quarters, which, though spacious, were rather plain. Beside his bed were photographs of his mother and younger sister Prairie Flower.

Parker extended generosity to any member of his tribe and hospitality to many influential people. Many famous people ate at Quanah’s table, including British ambassadors, an American President (Theodore Roosevelt), famous chiefs such as Geronimo and Lone Wolf, and General Nelson Miles. At the same time, Quanah fed any tribal person who came to his door. Such was his generosity that he died a poor man.

Quanah Parker is credited as one of the first important leaders of the Native American Church. I have heard several versions of Quanah’s introduction to peyote, most of them fantastical. I have sat up with modern day Comanche in NAC (peyote) ceremonies. The Comanche versions of Quanah Parker’s role in the Native American church is embellished and lends weight to his legendary status among American Indians.

I accept S. C. Gwynne’s version that Quanah, after having been gored in southern Texas by a bull, was cured by a “Curandera” who used peyote tea as an antibiotic. What I know to be true is that Parker was a “roadman,” as the peyote ritual leader is called. I know this because I have seen in the museum at Fort Sill several of Quanah Parker’s peyote fans. One of them was fashioned with magpie feathers. This fan is used specifically to ‘fan off’ participants after someone has died. Only a “roadman” uses such a fan.

There are two main altar styles in the NAC ceremonies: half moon and cross. Quanah was a proponent of the half-moon altar; in other words, the one not using a Bible in its teachings. Three years after Quanah’s death, the NAC was wisely chartered as a Christian denomination. It retains its legal status as a Christian Church to this day. The real point is this: Legal status as a Christian Church made the Native American Church the only pan-Indian “religion.” I see in that evolution the influence Quanah had in acclimating to white culture, and, yet, he maintained his Indian traditions and beliefs. His ability to change with the times and still retain his Indian identity underlies his legendary status.

Despite the savagery of Comanche assaults on settlers and soldiers alike, and Quanah’s youthful ruthlessness and hatred toward the society that killed his father and reclaimed his mother and sister against their will, Quanah was inherently good-hearted. Witness his generosity feeding and housing anyone who came to his door during his later “civilized” years. Witness his openness to reform and change. Witness his acclimatizing to the inevitable. But to maintain good-heartedness, a person requires personal freedom, intellectual independence and, most importantly, a life that is free from interference. When the cultural and organizational structures in which people live and work become oppressive, then a boxed-in, cornered people who no longer fear death will fight with savagery.

To my thinking, the reason Quanah Parker is a legend among his own people is because he did not fear death and because he was grateful for the gift of life, the privilege of Being, no matter the hardships. The reason Quanah is a legend in the histories of the dominant culture was because a brilliant, feared “savage” war chief transformed himself into a man who adapted to new realities, yet still retained influence as a power broker of the Southern Great Plains at the turn of the twentieth century.

The universal pattern in Quanah Parker’s heroic journey to wholeness and fulfillment is legendary but not mythic. Myths are creation stories. They describe the emergence and patterns of energy at the most fundamental levels. Joseph Campbell describes myth as “…the secret opening through the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into human cultural manifestation.” Empire of the Sumer Moon is not about a mythic figure. It is a true history in which a heroic figure, Quanah Parker, played a legendary role.

This reviewer’s love of American history and fascination with indigenous pre-Christian cultures has produced a review of Empire of the Summer Moon that is hardly critical. I realize that I have formed this review around a recount of some, but not all, of that history. I have concentrated on the Comanche and on Quanah and have left to future readers inspired by my review to discover the saga of Cynthia Ann and the grand sweeping panoply of Texas history that is also vividly rendered by S. C. Gwynne. I am by no means the only reviewer to use glowing words. “Transcendent…” is a description from the New York Times Book Review. Once I began reading this book, I couldn’t put it down. The history was revelatory, and the lyrically, novelistic style of the narrator was deeply satisfying.

I will say that Empire of the Summer Moon fell into my lap as a gift from a friend who knew I had been to Quanah Parker’s “Star House” in Cache, Oklahoma, and had, in 1989, attended an annual Parker Family Reunion Powwow (you can read all about the reunions on the Parker Family website.) At that time, I listened at length to Quanah Parker lore as related by his grandson, great-grandsons, and great-granddaughters. The opportunity to review this book was also kismet. I am not a book critic. I love literature, I love history, and I love American Indian folklore, and I loved this book.

I will relate one disappointment. Titles are context. S.C. Gwynne renders his entire narration within the context of Empire of the Summer Moon. He never explains why he chose that title. It seems obvious to me that the summer moon is significant to the Comanche. Which summer moon? What is the connection?

To all Indian tribes, the moon was their calendar, a major reference point. All Indian languages had separate names for each of the twelve moons in a year’s time. All Indian tribes also recognized that some years have thirteen moons. Often the thirteenth moon was called “the moon in the middle.” Among the forest tribes east of the Mississippi river, the thirteenth moon was usually placed following the winter solstice, and the great supplicating ceremonies were held in the dead of winter during the time of that moon. Among the Plains Indians, the moon in the middle followed the summer solstices and was usually the moon during which any given tribe held their great summer ritual, such as a Sundance. Although Gwynne describes none of the Comanche rituals, and this reviewer knows of none save for modern day Native American Church ceremonies, it follows in my thinking that there is some intense spiritual connection between the Comanche and the “Summer Moon.” Is the summer moon referred to in the title of this book the time when some Comanche ritual occurred—the ritual, perhaps, that would pray for another successful buffalo hunt?

Please, Mr. Gwynne, in your next edition, tell us the connection.

1 comment

Awesome. Just my type of book