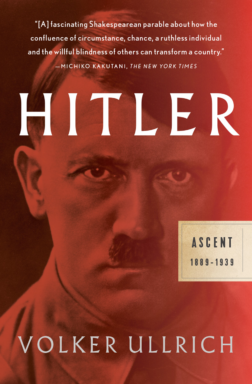

Volker Ullrich

Translated from the German by Jefferson Chase

As the son of a WW II veteran who fought in the Battle of the Bulge, I grew up hearing stories from my Dad about his personal experiences in the war. Later, in high school, I read journalist William Shirer’s Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (published in 1960), and in college I wrote a paper based on historian Alan Bullock’s biography, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1952). More recently, I read books about the siege of Leningrad (The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad, Harrison E. Salisbury, 1969) and the trampling of eastern Europe before and during WW II by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, Timothy Snyder, 2010).

I picked up Volker Ullrich’s Hitler: Ascent, 1889–1939 because I wanted to know more about Hitler the man: his roots, his formative years, his path to Führer, the choices he made along that path, and his relationships with the men and women in his life. I was hooked on the book after reading the Introduction, which I quote at length here.

This book does not pretend to offer a fully new interpretation of history. In light of the achievements of my predecessors from Heiden to Kershaw, that would be utterly arrogant. But I do hope that the first volume of this biography succeeds in bettering our understanding of the man Stefan Zweig described as “bringing greater disaster upon the world than anyone in our times.” In particular, I hope that Hitler’s personality emerges more clearly in all its astonishing contradictions and contrasts so that our picture of the man is more complex and nuanced. Hitler was not a “man without qualities.” He was a figure with a great many qualities and masks. If we look behind the public persona which Hitler created for himself and which was bolstered by his loyal followers, we can see a human being with winning and revolting characteristics, undeniable talents and obviously deep-seated psychological complexes, huge destructive energy and a homicidal bent. My aim is to deconstruct the myth of Hitler, the “fascination with monstrosity” that has so greatly influenced historical literature and public discussion of the Führer after 1945. In a sense, Hitler will be “normalized”—although this will not make him seem more “normal.” If anything, he will emerge as even more horrific.

Ullrich ends the Introduction with this warning:

Every generation must come to terms with Hitler. “We Germans were liberated from Hitler, but we’ll never shake him off,” Eberhard Jäckel concluded in a lecture in 1979, adding: “Hitler will always be with us, with those who survived, those who came afterwards and even those yet to be born. He is present—not as a living figure, but as an eternal cautionary monument to what human beings are capable of.

A historian, journalist, and author who has written biographies of Napoleon and Bismarck, Ullrich knows how to tell a story, and Jefferson Chase has done an excellent job of translating Ullrich’s German text into English. Ascent is an extensively documented scholarly work, with 211 pages of notes and 24 pages of photographs. Again and again, Ullrich lets his readers hear from his predecessors in the field. Sometimes he agrees with them, sometimes not.

“Why,” you might ask, “would I want to read this 758-page tome?” Here’s why: If you read Ascent, you will learn about a man who:

- was a megalomaniac with deep feelings of inferiority.

- had a “prodigious memory [that] ensured no insult would ever be forgotten.”

- was by age 30 years, the Nazi Party’s most effective public speaker. (In Mein Kampf, he wrote this about his first public speech: “I talked for thirty minutes, and what I used to sense internally without really knowing it was now confirmed by reality: I could speak well.”)

- “was addicted to the thrill of popular admiration.”

- “preferred younger women” and said in 1942, “A girl of 18, 19, 20 years is as malleable as wax. A man needs to be able to put his stamp on a girl. Women themselves want nothing different!”

- who described in Mein Kampf and many speeches exactly “what he would do if he came to power.”

- was underestimated time and again by his domestic and foreign adversaries.

- was a master of deception “whose primary personal characteristic was his infinite ability to lie.”

- “liked to depict himself as a man of the people, [but who] in fact despised the masses, which he regarded as nothing more than a tool to be manipulated to achieve his political ambitions.”

- cleverly and unscrupulously exploited social and political crises—for example, the “sudden impoverishment of broad segments of the German populace,” especially in rural Germany, as well as the crisis in democracy in inter-war Europe.

- grasped Germans’ fears of foreignisation as a result of immigration (of Jews from eastern Europe).

- convinced Germans that he would make Germany great again, as in “Deutschland über alles.”

- was a self-admitted “fool for technology” who made flying tours of Germany during political campaigns and, with propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels and the filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, used radio and film to great effect. Riefenstahl’s film about the 1934 Nuremberg rallies (“Triumph of the Will”) and her two-part film about the 1936 Berlin Olympics (“Olympia”) are both available on YouTube.

- was ushered “through the doors of power” by conservative elites in Germany.

- “loathed bureaucracy and did not think much of appointments.”

For me, Ullrich’s book could be a manual for a small group of dedicated miscreants wishing to take control of a democracy. To be sure, no two historical eras or democracies or leaders are identical, but the human organism has not evolved significantly in the past 5,000 years. Rather, it has been social organizations and institutions that have changed—and they can change again.

For that reason, I also see Ullrich’s book as a cautionary tale for all citizens in democracies. The Irish politician John Philpot Curran said, “The condition upon which God hath given liberty to man is eternal vigilance; which condition if he break, servitude is at once the consequence of his crime and the punishment of his guilt.”

Or, put another way: Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.

1 comment

This sounds frighteningly similar to the 45th president of the United States of America.