Medical memoirs are a popular genre. From Oliver Sacks’ vivid case studies, to doctor-turns-patient stories such as Paul Kalanithi’s acclaimed When Breath becomes Air, to wild stories from the emergency ward. Yet the best medical memoirs are not acts of voyeurism but rather compassionate accounts about life and death and our frail humanness.

One Curious Doctor is more than this. Hilton Koppe opens a window into the inner world of a family practitioner through a focus on the doctor/patient relationship and deep self-reflections on the complexities and mysteries of attending to the living and the dying. What exactly is this thing – a relationship between a doctor and a patient?

About halfway through One Curious Doctor there is a sentence that pulled me up sharp: ‘It is okay to be a doctor and be human’. Hilton wrote the sentence as a reassurance-to-self, as if the opposite might be closer to the truth: ‘It is not okay to be a doctor and be human.’ The book asks us to consider where exactly family practitioners should sit on the continuum between clinical distance and human connection. There are stories of death and healing and deeply explored questions about what role doctors can, do, and should play in the profound moments of their patients’ journey. It challenges us to reconsider the conventional wisdom that a doctor/patient relationship is straightforward.

In 2019, after 33 years in practice, Hilton was diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder – accumulated vicarious trauma from working as a family practitioner. “Why me?” he asked himself, “why not my colleagues?” Was it solely related to work or was there an intergenerational aspect to the trauma? Had his migrant experience and family background fleeing Europe from the holocaust contributed?

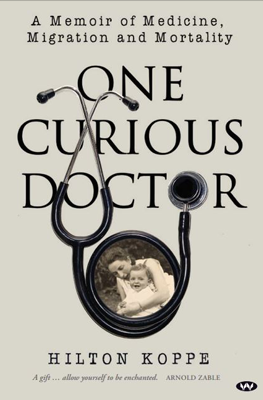

One Curious Doctor is more than a medical memoir, both in its subject matter and in its literary forms. It is a potpourri of memoir, poetry, family history, diary entries, photographs and speculative journaling. The pieces – certainly not chapters in any conventional sense of the word– play with form. Fonts change, prose slips into poetry, pages are laid out differently. We move from patient stories to family history, from Lithuania, to South Africa to Australia.

You will find a conversation between two sports commentators describing a gruelling day in the life of a tired country doctor as if it were a football match. There is a wonderful poem called ‘Ode to my Stethoscope’ that beats with auditory allusions and imagery. There are imagined diary entries from unknown relatives in Lithuania and Germany. Unknown because the Holocaust cleaved Hilton’s family into those that escaped and those that didn’t.

Hilton began writing well before his PTSD diagnosis and subsequent retirement from clinical practice. He wrote as a way of processing challenging experiences as a doctor. “When patients I felt close to died, writing helped me move forward.” Many of the pieces in One Curious Doctor were written long ago, sometimes as exercises purely in creative and improvisational writing.

Reading One Curious Doctor has changed the way Irelate to my own doctor. Even inside the shortest 15-minute visit, we squeeze in a quick chat (often as we walk to the door) about what we are both reading. I know it matters, because at the next visit we pick up the conversation and share our reviews. Even if six months have passed, he remembers. At the last visit we talked about art.

Yes. It is okay to be a doctor and be human.