“I only liked Perestroika when it first started. If someone had told us back then that a KGB lieutenant colonel would end up as president …” [ellipses in the original text] The sentiment of this quote, from the chapter “Snatches of Street Noise and Kitchen Conversations” (2002–2012) of Secondhand Time, is shared by many citizens of post-Soviet Russia (or Russian Federation as it is officially known).

Here is another quote from the same section of the book: “At the end of the day, I’m an imperialist, yes. I want to live in an empire. Putin is my president! Today, it’s shameful to call yourself a liberal, just like it used to be shameful to call yourself a communist.” And here’s another quote, from the period 1991–2001: “With socialism, the people were participating in History … They were living through something great …”

I picked up this book for two reasons. First, I wanted to know more about the post-Soviet “person on the street” in her own words. I had read two excellent books about the Soviet Union, both of them focused on political history and war: Timothy D. Snyder’s Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, where “between” refers to those nations unfortunate to have been sandwiched between Germany and the Soviet Union; and Harrison Salisbury’s The 900 Days: The Siege Of Leningrad, an account of Germany’s attempt to starve Leningrad’s population during World War II. Snyder and Salisbury give their readers a clear sense of the scale of human suffering wrought by war, but their accounts are of events that occurred more than 70 years ago. I wanted to know what men and women today have to say about post-Soviet Russia.

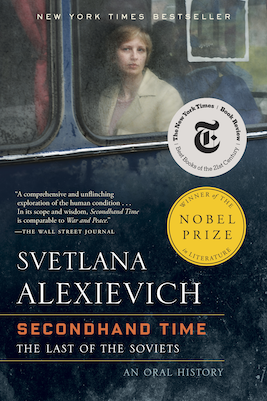

My second reason for picking up Secondhand Time is that its author, Svetlana Alexievich, a Belarusian investigative reporter, was the 2015 Nobel laureate in literature. Believe me, those pesky Norwegians and Swedes know how to pick a winner. She didn’t disappoint me.

For this history of the 21-year period 1991–2012 during the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Alexievich listened to the stories of thousands of men and women. Some of them lived through the 1920s, while others weren’t born until perestroika in the 1980s. Alexievich deftly balanced these diverse opposing voices and gave me a sense of the ongoing churning in Russia today.

The three quotations at the beginning of this review justly illustrate three positions in today’s Russia. 1) Many Old Soviets had pursued the promise of a socialist utopia of equality and sacrificed again and again for a future reward, only to witness the takeover of their country by oligarchs, thieves, and thugs in the 1990s. 2) Other Soviets were ready for democracy, embraced perestroika, but have been disillusioned by what it has brought them. 3) Many Russians want to see Russia return to its proper place as a world power, as a country that is respected and feared by other nations.

Is it fortuitous that the English translation of this book was published in 2016, in the midst of a U.S. presidential campaign in which “make America great again” is a prominent slogan? As I read Secondhand Time, I was struck by how much many Old Soviets long for some of the same things that many Americans do: a strong leader (even a man such as Stalin), prominence on the world stage, a time when their lives and work mattered, and a fair shake from their government.

If you want to go beyond conventional news sources and learn about the complexity of life in Russia today—and its eerie parallels to life in the U.S.A.—you will find Secondhand Time very rewarding. If your local library doesn’t own it, suggest that they order it. It’s a book that more of us need to read.

1 comment

Intriguing review and definitely going to add this book to my “to-read” list. Thank you!