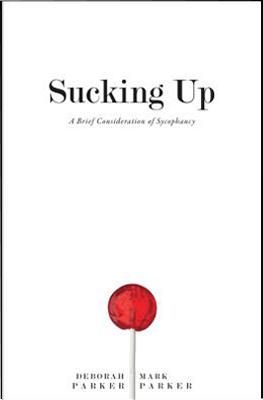

Sucking Up is the third book by coauthors Deborah Parker, professor of Italian at the University of Virginia, and Mark Parker, professor of English at James Madison University. Their two previous efforts focused on Dante and film, respectively. Both authors are steeped in the humanities, the field that studies the human experience. Their academic pedigrees and previous work enabled them to write this scholarly work, with citations, a notes section, and an index. In this slim volume of 127 pages (print edition), the authors use their complementary knowledge of Dante, film, the Italian Renaissance, and English literature to give the reader sharp examples of sycophancy in a range of genres, including literature, the stage, film, visual arts, and science.

The examples show that sycophancy typically involves three players: the sycophant (the person who is sucking up), the sycophant’s target, and the observer(s). One such example is the public prelude to President Trump’s first full cabinet meeting on June 12, 2017, during which he asked each member of his cabinet to name their position. When it was his turn to speak, Vice President Mike Pence (the sycophant) said to President Trump (his target), “It is just the greatest privilege of my life to serve as vice president to a President who’s keeping his word to the American people and assembling a team that’s bringing real change, real prosperity, real strength back to our nation.”

The observers included everyone in the room—other cabinet members, guests (e.g., Steve Bannon and Jared Kushner), and reporters—as well as the digital audience who viewed the event live or recorded. The approximately eleven-minute round of introductions was reported heavily, but we don’t know what each of the observers, especially those seated around the table, was thinking (as an observer) as the other cabinet members were making their own statements.

Most, if not all, of us have played the role of observer, hence our familiarity with the term “sucking up.” What we may not be so good at is recognizing when we are being a sycophant ourselves, or the target of one. I am grateful to the coauthors for giving me a set of lenses to help me examine myself—my actions, motives, and my experience as a sycophant—and then to understand myself better.

Also, I look forward to learning more about other examples cited in Sucking Up, e.g., in the novel David Copperfield; in the films, Sweet Smell of Success and All About Eve; and in the play King Lear. In the latter three, the authors show how sycophancy can be destructive, even lethal. For example, in Act I of King Lear, the King asks his three daughters, “Which of you shall we say doth love us most?” The action ensues, and by the end of the play, the royal family—the sycophantic daughters Goneril and Regan; their sister Cordelia, who chose silence instead of sucking up; and King Lear—are dead. Parker and Parker conclude, “Sycophancy carries the day.”

The authors’ timing could hardly have been better, given what’s happening in Washington, D.C. If you’d like to see more clearly, and perhaps understand better, what’s happening, I heartily recommend reading Sucking Up.