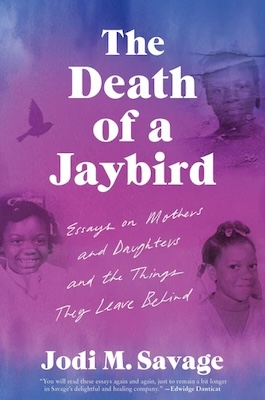

Across cultural heritage, certain kinds of courage endure. One of them is at the core of Jodi M. Savage’s collection, The Death of a Jaybird: Essays on Mothers and Daughters and the Things They Leave Behind. Ms. Savage and I come from different traditions, yet her skill, candor, and insights marched into my heart. She forges an immediate, strong bond between author and reader. Hers is a deeply generous work that inspires not only admiration for her, but gratitude.

Ms. Savage is a lawyer by training and experience and is currently studying for her M.F.A. at New York University. She brings a range of expertise to her writing – the most powerful being how to fashion a stunning blend of titanium honesty and the capacity to love, both alongside humor. There is a great deal at stake in this collection. If the reader cries in recognition, so be it.

The first essay introduces a motif: “When I think of Black Lives Matter, I think of . . .” On each return, this refrain invokes Ms. Savage’s grandmother, the woman who raised Ms. Savage when it became clear that the cocaine habit of Ms. Savage’s mother – Granny’s daughter – was not a passing phase. These pages celebrate Granny’s spirit, decline, death, and profound influence, and set up the collection’s remarkable trajectory. It tracks three generations of Black women who love and confront their way through adversity – recognizing, in the end, the difference between clarity and punishment. Throughout, Ms. Savage’s ability to synthesize meaning guides the reader. Telling stories in first person, she becomes a Greek chorus of one, sharply observing the collection’s actors, herself, and us.

The first essay’s opening line, “When I think of Black Lives Matter, I think of my grandmother,” juxtaposes the current movement with earlier generations and the enduring, painful common ground between them. In the middle stands Ms. Savage herself. She grapples with Granny’s nighttime 911 calls, delusions, intermittent lucidity, and slide into Alzheimer’s. Ms. Savage delivers family history leanly and frankly while maintaining an ongoing storyline of Granny’s outreach to law enforcement – grounded in a police kindness Granny has experienced since childhood and which creates her personal holy trinity of “Jesus, Barack Obama, and a police officer.” This is by no means Ms. Savage’s trinity. Yet she highlights the compassion of a white officer who treats Granny’s hallucinations gently and asks her whether, if he takes the phantom children she conjures to the hospital, she will follow to make sure they’re okay. The ploy to get Granny into a medical setting works, and Ms. Savage regrets not knowing the officer’s real name, as she wishes to thank him for treating her grandmother not as a threat, but as “who she really is: sick, afraid, frustrated, human.”

Despite one officer’s kindness, though, risk echoes. True to her legal training, Ms. Savage presents evidence that places Granny in a toxic, racist system. From across the country, and embedded in the first essay, lie succinct, factual accounts of Black Americans with mental health difficulties who have been summarily shot to death during police visits meant to help them. In caps, headlining each account, are the name, age, diagnosis, location, and date of death of each such victim. The headers read like tombstones. They inhabit the ground over which Ms. Savage and her grandmother walked daily.

Tenderness is never far from Ms. Savage’s courage. While she bears witness, provides context to the reader, and connects her family to the breadth of human grief, she describes in accessible, personal terms how she manages Granny’s phantoms – with patience and exasperation, humor and sly distractions. She steers Granny within the logic of her delusions, telling her she can feed imaginary children visitors later, when they’re hungry; or takes away a baseball bat to save both Granny’s invisible intruders and, frankly, the family’s furniture. Ms. Savage allows us into her vulnerability when, after a long day at work, she wakes up to officers in the middle of the night while she is in her “bedtime glory” – headscarf, clay face mask, well-worn T-shirt. Still, she must ultimately make 911 phone calls herself to get Granny the medical help she needs. Within a callous system, Ms. Savage resists sacrificing ethical ground or dignity, right up to the moment when she closes Granny’s eyes and says, “Sweetie, it’s finally over.” Black Lives Matter, and it mattered how Granny died.

In subsequent essays, Ms. Savage takes us into rich, difficult spaces that shaped her before and after Granny’s death – and that of Ms. Savage’s mother, Cheryl. The initial frame of Granny’s death supports many conversations, including how to attend a Black funeral. Throughout, tasty detail peppers the wit of Ms. Savage’s familiar, narrative voice. She speaks to us as a friend or colleague, allows us to hear the private language of her family, then pulls up to thirty thousand feet to pull it all together.

“Searching for Salvation at Antioch” introduces the size of Granny’s personality as a populist preacher in her younger days and explores the church misogyny Ms. Savage rejected. The Pentecostal faith was Granny’s salvation, but it was Ms. Savage’s curse. Treasuring Granny, nevertheless, Ms. Savage searches for salvation on her own terms. In the end, because Granny’s church was inseparable from her, Ms. Savage honors that faith legacy as something even Alzheimer’s cannot not steal. She embraces the complex, loyal, humanly flawed gift that was Granny’s love. Unfinished business about their having endured sexual abuse from third parties lies between them. Yet, Ms. Savage says, “[i]n life, we must learn to accept the apologies we will never get.” It may be difficult to describe one’s hero this way, but that is what Ms. Savage does.

Contrast arrives with the third essay. The title, vivid specifics, and lighthearted tone of “How to Attend a Black Funeral” exhort diverse readers to consider an instructional list – lists are effective throughout this collection – that is clever and real. The list announces the funeral as a homegoing, a multi-hour production of costume and tribute, the funeral program a life-defining document suitable for enclosure in a time capsule. If there are gaps in the funeral program’s information, no worries. Gossip can fill them in. Celebration and repast will follow. I’d forgotten how flat-out funny this essay is. I can’t help recalling tales of old-time Greek Orthodox women – wailing or hired to wail at a funeral and who, perchance in a flourish at no extra cost, throw themselves onto the casket as it descends into the grave. Or so went the tales of village mourning I overheard as a child. Ms. Savage does more than claim her own tradition in “How to Attend a Black Funeral” – she invites us in.

The powerful “Running Out of Time” begins with humor of a tougher variety: “There are two times when families are most likely to show the entire circumference of their asses: in sickness and in death.” Ms. Savage’s mother Cheryl appears. Ms. Savage cautions against framing this essay in the comfy marketing language of reconciliation – in which generations of women characters in a beach read find “acceptance and forgiveness” and lay bare “the human frailties that connect us all.” Too easy. The truth is, Ms. Savage says, her mother was an addict. And once again, Ms. Savage is in the middle.

For those of us who have witnessed a loved one’s addiction or death from it, this essay hits home. We have not all experienced what Ms. Savage’s Black family did – witness the humiliations delivered in a largely white medical system – yet she nails what some in her readership will recognize: “Drug addicts aren’t reliable, even when they love you.” This refrain appears three times in the essay. It is true every time. Ms. Savage’s insight is worthy of awe.

Here is a youngster who once wanted to become an infectious disease specialist after working in a New York City AIDS hospice with too-young patients; a member of the high school division of the National Society of Black Engineers; a young woman who refused to move Granny to a family-adjacent Florida nursing home but, rather, took on cherishing and caring for Granny in their shared Brooklyn house; who dealt, in elementary school, with her mother’s repeated abandonments, poor health, incarceration, and more; who threatened to call the cops should her mother insist on coming to live in the household uninvited; who traveled to see Cheryl after her breast cancer diagnosis; who brought her estranged father together with Cheryl for the first time in a three-way phone call and its playful, profane, deeply affectionate exchange; and treasured Cheryl’s birthday cards, endearments, and clear longing and inability to be a full mother.

Ms. Savage delivers all this in short scenes that ignite her realities. Perhaps because there is no self-pity involved, the reading experience is deceptively easy until the gravity of the content hits. Ms. Savage makes us understand that she never lacked mothering because she had Granny. It’s just that, for Ms. Savage, there were two mothers involved in a complex dynamic. She learned to take care of herself. With Cheryl, she set boundaries while eventually opening the door where she could. Meanwhile, having vowed not to be like her mother, Ms. Savage navigated Barnard, law school, working as an attorney, and eventually writing The Death of a Jaybird. Remarkably, despite the high emotional costs Ms. Savage must have paid, what does not appear in this work is even a shred of resentment about caretaking Granny. Never once does Ms. Savage say, “Oh, these women squashed my dreams. I couldn’t get ahead in my career. I couldn’t have what I wanted.” She seems never to consider herself as someone entitled not to be bothered or, to use a hackneyed phrase, entitled “to have it all.” “All” showed up unadorned and she handled it – partly thanks to an ancestral cohesiveness that humbles mainstream self-centeredness.

The remaining essays come at grief and daily life from different angles – and yes, advice lists. Ms. Savage’s writing is an act of reclamation, tribute, and plain talk in the constant presence of racism. Yet she reaches across chasms. She offers specifics to make you laugh out loud just when you thought you were going down a dark road. Her work strikes me as the transfer of love across the territory of the irreconcilable. And just as the saying “death of a jaybird” is meant to invoke a sudden humiliation, Ms. Savage works against it, granting dignity to herself, Granny, and Cheryl.

I started by asserting that, across cultural heritage, certain kinds of courage endure. Ms. Savage brings forth such courage to see loved ones for who they are. In his poem, “A Great Wagon,” Jelal al-Din Rumi says, “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing/There is a field. I’ll meet you there.” Ms. Savage has found that place.

Full disclosure: Ms. Savage and I attended the 2021 Storyknife Writers Retreat but maintained different writing schedules. At that time, we did not read one another’s work, as much of it was incomplete.