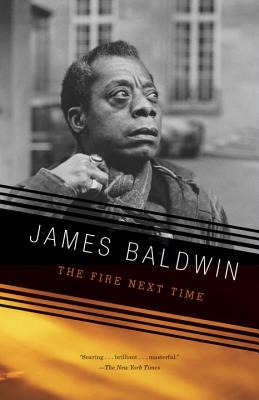

“Color is not a human or a personal reality; it is a political reality.”

— James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

“The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.”

— W.E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folks

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin was first published in 1963 during the emerging Civil Rights Movement and was an instant best seller. A brilliant social critic, public intellectual, and interpreter of racial myths and beliefs, Baldwin captured the zeitgeist of a country riven by race. Without prejudice or fear, he deconstructed the institution of racism in America.

What has been called Baldwin’s “eloquent manifesto,” The Fire Next Time is an admixture of autobiography and confession, history and observation, and inside its pages Baldwin recounts his growing up in a Harlem ghetto, suffering the ambient fear in the societal stratum to which he belonged in the 1930s and 1940s. In his fourteenth year he confronted what could only be called an existential calamity: An awakening so severe that he feared for his life and sought refuge in the church.

Baldwin is forthright in The Fire Next Time about the dispute he has with his country. His dispute is revealed in two parts: in “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation,” and in an extended essay, “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind.” It is in the latter that Baldwin’s disputatious perspective is most effective and clear-eyed: Addressed to the reader, the letter is Baldwin’s cri de cœur brewing in a region of his mind.

“Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind” begins when he was a fourteen-year-old teenager confronting life as a black boy living in Harlem. Then, he had what he calls a “prolonged religious crisis.” He was afraid of the evil within and without, and he became aware of the despair in the boys who were his friends and those who were not; in the boys who were encouraged by their fathers—and his own father—to leave school and go to work; and, most of all, in his own life that catapulted him into the safety of the Christian church.

It turned out, then, that summer, that the moral barriers that I had supposed to exist between me and the dangers of a criminal career were so tenuous as to be nearly nonexistent. I certainly could not discover any principled reason for not becoming a criminal, and it is not my poor, God-fearing parents who are to be indicted for the lack but this society. I was icily determined—more determined, really, than I then knew—never to make my peace with the ghetto but to die and go to Hell before I would let any white man spit on me, before I would accept my ‘place’ in this republic. I did not intend to allow the white people of this country to tell me who I was, and limit me that way, and polish me off that way.

Baldwin admits, however, that no matter how much he internalized his determination to escape the dangers he found in the ghetto, every boy like himself faced the peril of their very existence and he needed to find something, a “thing” or a “gimmick,” to “lift him out.” He wasn’t athletic, couldn’t dance or sing, and writing as a profession wasn’t probable, even if it were thinkable. His interpretation of the world was experiential, conditioned as a black boy to be afraid and simultaneously to be “good”; to be always aware that the authority of his parents or his elders couldn’t protect him from the “nameless and impersonal, infinitely harder to please, and bottomlessly cruel” authority of white society; and never to escape the “terror” he felt awaiting “his mysterious and inexorable punishment.” He understood the source of his profound fear but, it seems, the articulation of it came after the fact: “That summer, in any case, all the fears with which I had grown up, and which were now a part of me and controlled my vision of the world, rose up like a wall between the world and me, and drove me into the church.”

Baldwin’s internalized fear stemmed from two sources: The fear he heard in his parents’ voices when he crossed a boundary they considered off limits; and the fear that could put a child on “the path of destruction” if he challenged the supremacy of white society. He heard a pervasive fear in his father’s voice when his father realized that his son James “really believed” he “could do anything a white boy could do, and had every intention of proving it.” It didn’t really matter in the end whether James believed he could transgress the barriers between his world in Harlem and the white world outside. Believing and doing were the antipodes of his existence.

That summer seemed to be the starting point of a slow-moving bifurcation of his life before and his life after. A friend who had been saved and was concerned about the health of Baldwin’s soul, introduced Baldwin to the pastor of his church, a woman who, when Baldwin was introduced to her, smiled and said, “Whose little boy are you?” Harassed by the pimps and racketeers on “the Avenue” and wracked by a combustible mix of shame, fear and guilt, he surrendered to the pastor’s church, the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly, desperately wanting to be “somebody’s little boy.”

Perhaps it is not too farfetched to infer that Baldwin’s future as a writer lay in his decision to join the church when he was a young teenager. He does not say so explicitly in The Fire Next Time, but that summer he experienced a crisis so existentially profound that the parishioners determined that he had been “saved.” The guilt and fear precipitating his crisis “came roaring, screaming, crying out, “ Baldwin writes, “and I fell to the ground before the altar.” One moment he was clapping and singing and the next moment he was on his back, the parishioners looking down at him. On the floor that night, he found no answer to the question he asked of God: “If His love was so great, and if He loved all His children, why were we, the blacks, cast down so far?” He was, however, relieved of the guilt he had suffered, but he didn’t have the awareness or understanding to ask “why human relief had to be achieved in a fashion at once so pagan and so desperate—in a fashion at once so unspeakably old and so unutterably new.” Perhaps he became a writer many years later to answer the question he couldn’t answer then.

In this church, Baldwin found refuge not only from “the Avenue” and his guilt but also from his father. It was the vehicle through which he could immobilize his father’s hold over him, and at the same time compete with him. He became a “Young Minister” and preached for more than three years, drawing larger crowds than his father, who was a minister in a different congregation. Whether the competition was any more fierce than a typical relationship between a teenage son and his father Baldwin does not say, but he relished the privacy that his preaching and his studies afforded him, and, in particular, “the relative immunity from punishment” and days when he “could not be interrupted—not even by my father.”

Even as the young Baldwin saw his preaching as a way to keep his distance from his father, it paradoxically also immobilized him, something he wasn’t conscious of until later when he began to fall away from the church. As long as the excitement and intoxication of the pulpit and congregation—the sermons, the music, the pain and joy—kept him inside this comfort zone, he and the church were one.

Falling away from the church and his beliefs over those three years was a gradual process. Enrolled in a Jewish high school at sixteen, he had two formative experiences that he relates in The Fire Next Time. First, he read that men had written Jesus and the Gospels into historical texts, which forced him to question his religious and spiritual beliefs. Second, he took his best friend who was Jewish to his house and introduced him to his father. Afterwards, his father asked if he was a Christian and if he had been saved. The young Baldwin told his father that his friend was Jewish. Baldwin describes what happened next: “My father slammed me across the face with his great palm, and in that moment everything flooded back—all the hatred and all the fear, and the depth of a merciless resolve to kill my father rather than allow my father to kill me—and I knew that all those sermons and tears and all that repentance and rejoicing had changed nothing.”

Now, the battle was in the open, Baldwin writes, “and a more deadly struggle had begun.” For him, it was an awakening to the illusion of the pulpit; to the hypocrisy of his value to the pimps and racketeers on “the Avenue”; and to the exploitation of the congregation to extract money from them. He felt lonelier, more vulnerable, and “just as black as I had been the day that I was born.” He had seen too much, too, and could no longer believe in it. Where was the loving kindness? Where was the love for everybody? What was the purpose of his salvation “if it did not permit me to behave with love toward others, no matter how they behaved toward me?”

Baldwin’s ministry in the church, his Jewish friends, his difficult relationship with his father, and his feelings of inferiority coalesced into what seems to be a defining guide for the rest of his life:

It is not too much to say that whoever wishes to become a truly moral human being (and let us not ask whether or not this is possible; I think we must believe that it is possible) must first divorce himself from all the prohibitions, crises, and hypocrisies of the Christian church. If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God cannot do this, then it is time we got rid of him.

Although the structure of The Fire Next Time is in the form of two letters composed as essays—the first to James, Baldwin’s nephew, and the second to the reader—the letters tell stories in three sections, each one connected to the other through Baldwin’s probing mind and inimitable stylistic genius. The first section describes and analyzes his fourteenth summer when his fear, guilt, and rage overwhelmed him, and he found safety in the church where he began a three-year revivalist ministry, as discussed above. In the second section, Baldwin describes his visit to Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, at his mansion in Chicago. Although he was drawn to the leader’s charisma and his “peculiar authority,” he knew he would never accept the teachings of the Nation of Islam. In the third section, Baldwin presents an incisive counterargument to the Nation’s teachings through an examination of the historical presence of black people in America, the necessity for change, and the hope for renewal.

Baldwin’s rejection of the Nation’s ideology that white people were cursed with the devil; that all black people belonged to Islam; and that the chosen of Allah would be separated from this “doomed nation” held no truth for him. He perceived that black people belonged nowhere other than in America where they were bought into slavery and where they must demand their freedom and equality—they had neither counterparts nor predecessors anywhere else.

But in order to change a situation one has first to see it for what it is: in the present case, to accept the fact, whatever one does with it thereafter, that the Negro has been formed by this nation, for better or for worse, and does not belong to any other—not to Africa, and and certainly not to Islam. The paradox—and a fearful paradox it is—is that the American Negro can have no future anywhere, on any continent, as long as he is unwilling to accept his past.

America must resolve what W. E. B. Du Bois called “the problem of the color line.”

In the third section Baldwin addresses not only the historical precedents of racism but also how the myths, beliefs, and stereotypes of racial behavior in politics, society and culture distort the wholeness of human beings and deepen their oppression. Dismissing the atavistic notion that black people were only three-fifths of a human being, Baldwin sheds light on the bewildering incompetence of such a notion: “There is absolutely no reason to suppose that white people are better equipped to frame the laws by which I am to be governed than I am. It is entirely unacceptable that I should have no voice in the political affairs of my own country, for I am not a ward of America; I am one of the first Americans to arrive on these shores.”

There also is no reason to believe that white people have more intrinsic value than black people, or that black people would want it in any case. Likewise, there is no reason not to believe that “love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” Baldwin himself wouldn’t have minded taking off his mask when he was dining with Muhammad. White people weren’t his enemies, and he didn’t want to be separated from them. As a matter of fact, Baldwin thought: “I love a few people and they love me and some of them are white, and isn’t love more important than color?”

Baldwin’s clarity is unmistakable in The Fire Next Time. He envisions a different resolution to the historical memory of racist precedents embedded in America’s culture: They can be changed, transformed, and with hard work transcended. For the sake of his country America to become one nation, Baldwin writes, “We, the black and the white, deeply need each other—if we are, really, that is, to achieve our identity, our maturity, as men and women.” He knew how onerous it would be to change the dynamics of racism and racist thought and behavior. Still, he hoped that people could find a way to emancipate their minds and bodies from the pathology of oppression that continues to live on in America’s DNA.

Baldwin’s hope for renewal and transformation was not misplaced in 1963, but he would not have been surprised at the distempered recrudescence of nationalism and the purveyors of racist ideology in the first quarter of the twenty-first century. He would have written a critical analysis of the falsehood that President Barack Obama ushered in a post-racial or colorblind society. He would have probed fearlessly the structural violence in America’s political, societal, and cultural institutions, such as in mass incarceration, housing and educational segregation, health care, poverty, and voter suppression. He would have corroborated and borne witness to the legitimate grievances of the Black Lives Matter movement. And, as the recent satirical horror comedy Get Out shows so effectively, he would have unmasked white racist innocence—a motif he deconstructed in The Fire Next Time fifty some years ago.