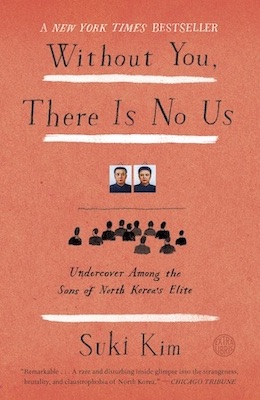

In 2011, the Korean American writer and teacher Suki Kim taught English to the sons of North Korea’s elite for two semesters. When it came time for her to leave North Korea (the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) and return to the U.S., she was moved by her students’ sorrow at the news of her departure. It reminded her of the words from a patriotic song, “Without You, There is No Us,” that university students in North Korea sing in honor of their “dear leader,” the ruler of North Korea, who at the time was Kim Jong-il and the “You” in the title. The words would become the title of the book she wrote about her time in North Korea.

Suki Kim was born in South Korea (Republic of Korea) and moved with her family to the United States when she was thirteen years old. She grew up in the New York City metro area and is a naturalized American citizen. Kim’s debut novel, The Interpreter, a murder mystery published in 2003, earned several awards, including the PEN Beyond Margins Award and the Gustavus Myers Outstanding Book Award. These awards honor works that address, respectively, issues of ethnic / racial diversity within the community of writers and the root causes of bigotry.

Like so many other families on the Korean peninsula, Suki Kim’s family was torn apart during the Korean War. On June 25, 1950, when North Korean bombs fell on Seoul, the capital of South Korea, her mother’s family fled South. On their way out of the city, Kim’s seventeen-year-old uncle gave up his place on a truck to make room for children and women. His family never saw him again. Kim grew up hearing this and other stories about her family and their ancestral roots in a unified Korea.

Kim first visited North Korea in 2002 as part of a delegation of Korean Americans who were there for the celebration of Kim Jong-il’s sixtieth birthday. In 2008, she was assigned by Harper’s magazine to accompany the New York Philharmonic to Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea. During the latter trip, she learned about Pyongyang University of Science and Technology (PUST), an “international university [that] was being set up in Pyongyang.” All its faculty, she learned, would be foreigners.

Even though the university was still under construction at the time, Kim submitted an application to teach English there. She had never taught English per se but had taught creative writing in the United States and at Ewha Womans University in Seoul.

Kim arrived at PUST in the summer of 2011, taught for two semesters (Summer and Fall), and departed in December. Without You, There Is No Us was published in 2014. In both semesters at PUST, she taught English to first-year university students. In the Fall semester, she also taught English to “the counterparts—the people who read and approved all…teaching materials…thirteen men, mostly in their forties and fifties, and two women in their thirties.”

Her first-year students were in their late teens / early twenties, well behaved, and disciplined. They wore white or blue dress shirts, black pants, and ties to class. Noting that many of them already had at least a few gray hairs, Kim speculated that even these privileged children, born in the early 1990s, may have lacked adequate nutrition during The Arduous March (1994–1998), when floods, drought, and the collapse of the North Korean economy led to widespread famine.

Kim also noted that within this group of privileged students, she could identify two sub-groups: “The parents of the more privileged students all seemed to be either core members of the Party elite or prominent doctors” and lived in Pyongyang. Many students in this group had known each other for years and had fathers who had worked abroad. Students in the second group came from other cities and had parents who were doctors or scientists. Many students in both groups had no siblings.

All students at PUST were admitted on the basis of their academic merit and were studying science and technology. However, Kim and her fellow teachers were struck by their students’ general lack of knowledge, which, they suspected, was a result of their not having access to the internet or experience with the World Wide Web. For example, Kim wrote, “Once a student asked me if it was true that everyone in the world spoke Korean,” and it was “nearly impossible to make them understand words like passport and insurance” and Social Security deduction. When she gave them an assignment to write a letter applying for a dream job, it seemed that “the entire concept of making oneself marketable in the eyes of a prospective employer did not exist.”

Teachers were with their students in the classroom, on the athletic field, and in the cafeteria, where teachers were encouraged to share a table with three students, preferably different students at each meal. Students looked forward to such opportunities to practice their English and to get to know their teachers better. Kim looked forward to the opportunity to get to know the students in this more informal setting. Kim and her tablemates had such long conversations that they often were scolded by the woman in charge of the cafeteria for being the last ones there.

Kim sometimes caught students lying and found herself “growing increasingly disturbed by the ease with which they lied.” She sometimes felt as if she didn’t trust any of them. However, they weren’t always devious, and Kim developed a strong affection for them and had “simple wishes” for them: better food, fresh milk, warm clothes, and heat against the cold classrooms. The students returned her affection, giving her a rousing send-off complete with two songs, “Our Unforgettable Teacher” and “Song of Suki.”

Except for weekend trips to nearby Pyongyang for groceries and occasional trips to visit an apple farm, a Christian church, or a sacred mountain—always accompanied by minders—Kim and her fellow teachers were confined to the PUST campus.

Despite such restrictions on the movements of Kim and her colleagues, she experienced or saw firsthand evidence of the privations of life in North Korea: very cold classrooms, interruptions in electrical service, restrictions on privacy, no free time, and a chauvinist culture. On a bus trip to an apple farm, she saw people walking along the road whose “faces were ghastly, as though they had not been fed in years” and workers at a construction site “with hollowed eyes and sunken cheeks, clothing tattered, heads shaved, looking like Nazi concentration camp victims.”

“Living in Pyongyang,” she wrote, “is like living in a fishbowl. Everything you say and do will be watched.” The teachers at PUST soon realized how this scrutiny and their self-censorship sapped their energy. Always mindful of being in a fishbowl, Kim surreptitiously made and secured handwritten and typed notes of her observations and then copied them onto three USB sticks. She hid two of them in her room and always carried the third one with her.

Evangelical churches worldwide contributed more than $10 million to build PUST, and money from the evangelical Christian community paid its teachers’ salaries and other operating expenses. Kim wrote, “North Korea was the evangelical Christian Holy Grail, the hardest place to crack in the whole world, and converting its people would guarantee the missionaries a spot in heaven.”

Soon after Kim began teaching at PUST, she found herself hemmed in not only by the North Korean government but also her evangelical Christian colleagues. Thus, in addition to keeping her journalistic work a secret, Kim also had to keep the secret that unlike other teachers at PUST, she was not a Christian. To maintain her cover, Kim attended Bible studies on most evenings, as well as Sunday services.

Soon after Kim began teaching, she was warned not to “give press any information about PUST” after she left Pyongyang. Thus, she acknowledges in the last paragraph of the book, that her book Without You, There Is No Us “will anger the DPRK regime, the president of PUST, and my former colleagues there.” While expressing sorrow for causing such anger and distress, she concluded, “I feel a greater obligation, both as a writer and as someone deeply concerned about the future of Korea, to tell the stark truth about the DPRK, in hopes that the lives of average North Koreans, including my beloved students, will one day improve.”

The iBook version of Without You, There Is No Us includes a Crown Publishers “Extra Libris”—A Reader’s Guide for Without You, There Is No Us: Introduction; Questions and Topics for Discussion; and A Conversation with Suki Kim. In the conversation, Kim says, “My goal was to write a book that humanizes North Koreans.”

I think that she achieved her goal, especially with respect to her students. I say this as a retired college professor and administrator who worked with thousands of students over my forty-two-year career. Kim brought her students alive for me. They are now in their mid-to late twenties, beyond university and even postgraduate education, and entering their careers. I wonder where they are and what they are doing now, and I will carry their stories with me for the rest of my life.

Kim is pessimistic about the chances for unification of the two Koreas, calling such an idea a “fantasy.” In 1945, after thirty-five years of occupation by Japan, Korea was divided into north and south, occupied by the U.S.S.R. and U.S.A., respectively. That division, which many consider the last remnant of the Cold War, remains today. Forever an optimist and hopeless romantic, I hope that Kim is wrong about the prospects for reunification. In fact, I hope that Without You, There Is No Us may play a role, however small, in bringing North Korea, South Korea, and their superpower allies together to find a path forward for the Korean people, including the young men with whom Kim worked at PUST.

4 comments

Thank you for your comment. We know far too little about North Korea.

Thank you for this fulsome and generous review. I would like to read Kim’s book, if only because I value perspectives from those who have “been there, done that,” as opposed to folks like me who only pretend to understand foreign cultures. What I find most revealing is the tug of war between the opposing ideologies of the rigid, authoritarian RNK regime and the university’s Christian benefactors who naively believe Jesus will deliver godless communists to their fold. The missionaries too are rigid and should seek accommodation, but where is the engagement of secular forces not allied to either camp or official US national security priorities that could encourage such dialogs and defuse tensions? Does Kim say?

Thank you for your comments and questions, which we appreciate very much. Regarding your first question—”Where is the engagement of secular forces not allied to either camp or official US national security priorities that could encourage such dialogs and defuse tensions?”—I am not an expert in this field, so what I know I’ve learned from a cursory reading of press accounts of such efforts. However, I can say that as I read Kim’s book, I thought again and again of the North/South divide and the pain on both sides of it, and I could only imagine the many men and women on both sides who are working toward reunification. Also, I wondered again and again whether external forces are a help or hindrance toward reunification. As others have written, reunification of the Koreas will be more difficult that the reunification of the Germanys was, but it is still possible.

Thank you for bringing this book to my attention.