What little we know of prehistory comes from divining the remains and rubbish of hominids who didn’t write down what they were up to. The day may come when alien archeologists puzzle over what we were up to after books went extinct. Texts they encounter may refer to a thing called “Internet,” which they will then seek for. When it doesn’t turn up, they will go on to other things, wondering where all the stories went.

Once upon a time all our stories were invisible, weightless. For millennia, people passed them on by speech, song, and mime. Their stories had no tangible presence, unless you count neurons. There were no libraries except those that individuals had in their heads, no publications, no media at all, just here-and-now news, gossip, poetry and lore, orally transmitted across generations from parent to child and through time and space by migrating tribes and wandering bards and minstrels.

Writing gave weight to words, changing all that. From stylus on clay tablet, to quill on parchment, to pen on paper, to printed books, to typewritten manuscripts, stories became symbols on pages you could hold in your hand and, if you were properly trained, understand. Storytellers mostly type their texts now. Some still write in longhand, but that’s well on its way to becoming a lost art. And despite the fact that typewriters are relatively modern writing instruments, they too are almost history.

Of course, we still type, and now more than ever, just not on paper. It seems like paper, but our words straightaway become bits in data files we can’t see, touch, or interpret. We need machines to show or read them to us, machines that run on electricity and software logic that are a lot harder to master than typewriters.

The oral tradition got a temporary boost from telephony. With it, stories could be exchanged farther, wider, faster, and once again completely ephemerally. Until recently, that is. Now, more often than not, phone conversations mostly involve curt epigrams streaming soundlessly from the ether, ungrammatically deprecating human speech with staccato abbreviations, misspellings, chockablock with annoying caricatures. Welcome to the Text & Tweet storytelling era.

But we still tell stories aloud, sometimes using microphones and cameras to capture our performances. Some get taped and broadcast, others digitized into data files that can be played back pretty much anywhere, anytime. Embodied as bits delivered by electrons, our yarns course through wires, fibers, space satellites, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth to bark out the mouths of headsets and loudspeakers. Constantly the world hums with ephemeral narratives, billions and billions each day, much of them spam.

As in Neolithic times, such stories are invisible, merely masquerading as printed matter. We can print them out but mostly we don’t. Why use up ink over a Web page when we can easily share it? On said page extraneous matter—blurbs, pictures, menus, videos, links, ads—may vie for our attention. It takes a lot of instrumentation to play all that jazz. And so, Web pages have come to contain vastly more code—stories computers tell one another—than content.

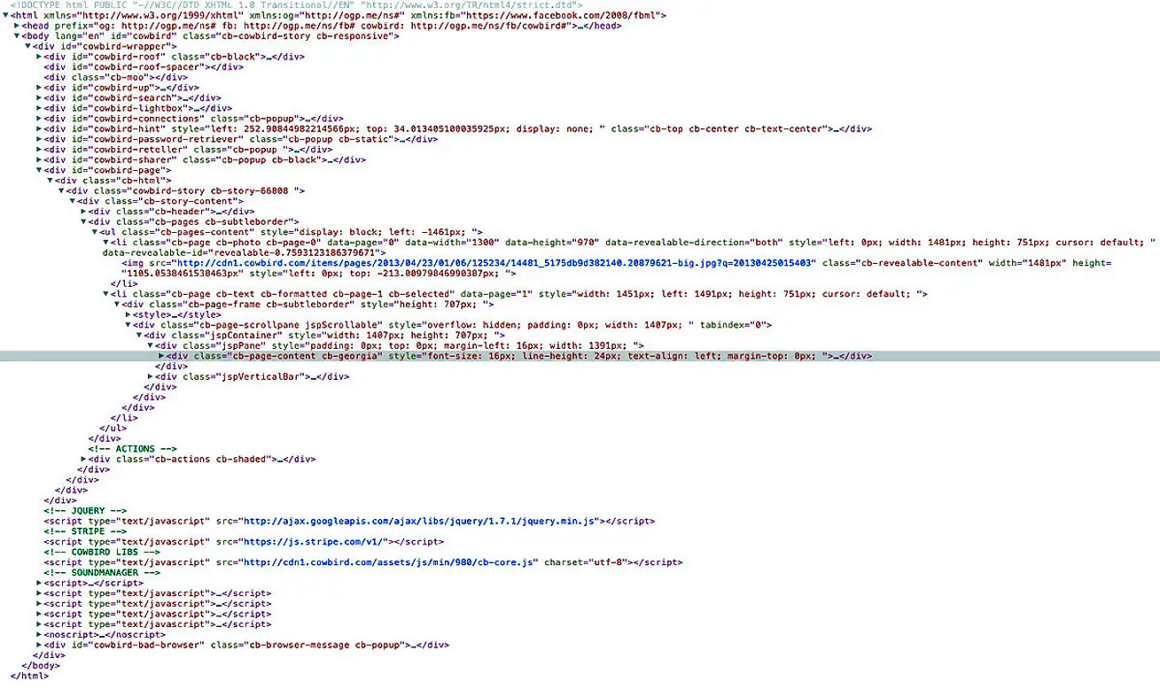

The first draft of this story was delivered to readers worldwide as a 127,000-byte Web page by a server in New York City in 2013. It was shorter then, just 590 words—3284 characters that took up nine lines of the web page, one for each paragraph. My text was nestled into 2400 lines of HTML and JavaScript code, comments and white space. The code displayed the document in a browser and managed the user interface widgets.

All of that code still wasn’t enough to make the page presentable. Another document (called a Style Sheet) handled that. That file provided 146,000 bytes of CSS code that every story on the site required to properly render.

The image above shows an outline view of that story as a Web browser sees it, with all blocks of code folded up so as to fit on the screen. The portion containing my nine lines of text is ensconced in that grey band running across the middle of the image. It wasn’t easy to locate the part I had written.

There are 88,000 stories archived at the writers’ community cowbird.com, where I posted my draft. If you peeked into the source code of any of them, it would look almost identical to mine, so identical that only two or three percent of content would differ from one story to the next. That’s just like our DNA, is it not? We celebrate our uniqueness in stories, but we are all pretty much alike on the biological level, and now so too have our stories become. I find this both comforting and scary. Comforting for how it expresses our basic commonality. Scary because of how devilishly complex online arts now are, opaque to any human creator’s ken. While traditional publishing is complex too, at least the book you see is what you get. It’s just ink on paper bound together, not bunches of bits embedded in semiconductors and an occult slew of itty-bitty components.

Like half the population, I have a blog. As websites go, it’s quite modest—a dozen pages and 60-odd posts, perhaps 60,000 words in all plus pictures. My site is powered by 20,000 files of PHP code sprawling across 600MB of server real estate—a thousand characters of code to support each one I’ve published so far. If one of those files gets bollixed up or goes missing, my blog could inexplicably fail (already has), and I’ll have to call in a geek (already did) to fix it. I love having the power to express myself but oh, the overhead! And even though I use or understand few of the features in the blog’s kitbag, I’ve bloated it with more than a dozen customizing add-ons. It’s the same craving for fiddly functionality that causes us to install silly little apps on our mobile phones.

In less than a generation, most of our communications have been virtualized, offloaded onto hidden machinery uttering gibberish in tongues of code, routing and ruling our interactions as roads rule where we drive. Going digital (was there ever a choice?) has accelerated the production and consumption of knowledge but also squirreled it away in whirring lockboxes wrapped in impenetrable layers of gnarly code. We hear so much happy babble about “disruptive technologies,” like smartphones, digital photography, social media, driverless cars, and cryptocurrencies, urgently obsolescing older ways of doing things, driven by an unslakable thirst for innovation, accelerating our lives at 4G, just as we’ve always been urged to hope would happen.

The new ways may be more capacious, efficient and groovy but also insanely intricate with amazing ways to fail (software bugs, disk failure, exploding batteries, not to mention financial crises) and to bite us (file corruption, identity theft, ransomware, mass surveillance). And as robust, resilient, and self-repairing as it may be, the Internet’s not invincible. A natural disaster or concerted cyberattack could disrupt enough satellites, ground stations, servers, switches and power grids to punch huge holes in the cloud and render our precious devices darkling glass bricks. Think Puerto Rico on a national scale.

Barring disasters, we will keep spinning invisible, weightless stories like ancient bards and raconteurs, their anecdotes, tales, poems and sagas now tweets, posts, lyrics and narratives, but weightlessly encoded into semiconductors, not our brains. If we hew to oral tradition, we can dictate stories. Our device will listen intently and decode our speech directly into digital prose. Its recipients, in turn, may ask their devices to read our stories aloud, as Alex (my Mac’s robot reader) does on this audio track. Bard in a box, so to speak.

Speaking of which, AI contraptions now routinely tell us stories. Artificial intelligence has been a computer science oddity for decades, but now that computers are powerful enough, networks vast enough, and data about anything and everything is ubiquitous, its day has come with a vengeance. Computers not only tell stories to one another in code, now they tell them to us in natural language; not just texts fed to them, but ones they generate on demand. What does this mean for human authors?

Feeling a bit threatened, I decided to check out AI storytelling and found my way to openai.com to meet ChatGPT. After logging in, I was faced with a text field at the bottom of the page beckoning me to type something. I prompted the machine to generate a piece of flash fiction: Please tell me a story about a woman who witnesses a child being kidnapped and what she does about it. Make it about 100 words long.

Straightaway came its 90-word reply:

As Sarah walked home from work, she noticed a young boy being dragged into a van by a stranger. Her heart pounding, she quickly memorized the license plate and called the police. With her quick thinking, the police were able to track the van and rescue the child within hours. Sarah’s bravery and attention to detail helped bring the kidnapper to justice and reunited the child with his grateful parents. From that day forward, Sarah knew the importance of staying alert and taking action when someone’s safety was at risk.

I asked that question because it is an inciting incident in a novel I’m working on (read excerpts at The Write Launch). What the AI composed hews to my plot line, except that the car is a sedan, not a van, my character is named Anna (which at least rhymes), and she photographs the license plate instead of memorizing it. Also, she had just left her place of employment. As that scene’s not online, it felt pretty uncanny, wouldn’t you agree?

Continuing, I typed: Thank you. Moving along, what happened when Sarah was called to testify against the culprit in a trial? Out came:

Sarah was called to testify against the culprit in a trial. Although she was nervous, she knew it was important to stand up for the child and make sure justice was served. As she took the stand, she recounted the events of that day and identified the perpetrator. The defense lawyer tried to discredit her testimony, but Sarah remained steadfast and truthful.

After hearing all the evidence, the jury found the culprit guilty and he was sentenced to many years in prison. Sarah felt a sense of relief that the perpetrator was off the streets and that the child and his family could begin to heal. She also learned that speaking up and being a witness was not only the right thing to do, but it could also make a huge difference in someone’s life.

This is quite similar to what transpired in my novel, except that the perpetrator did not go to prison. Nonetheless, my character did resolve to continue speaking out.

In Anna’s case, it was the prosecutor who was hard on her. Similarities aside, I found it remarkable that the AI could weave a story and extract a moral from it. In it, I see a tendency to create a happy outcome; after all, the story could have been a lot darker. But at least it stayed in character, having given that character a name. It wrote in third person close, describing Sarah’s private feelings.

I asked why there isn’t any dialog: I notice that your story does not include any dialog. Was that a choice you deliberately made?

Yes, that was a deliberate choice I made in crafting the story. Keeping the story concise and to-the-point at just 100 words, I focused more on the actions and emotions of the main character, Sarah, rather than on any dialog that may have taken place. Additionally, a story without dialog can be interpreted and imagined in different ways by the reader, allowing them to fill in the gaps with their own imagination.

After several more prompts for stories, I concluded that the stories the system had concocted weren’t all that stunning, but good enough for commercial fiction. And surprisingly, when I submitted text ChatGPT had generated to a service at writer.com that purports to detect AI-written content (try it yourself), every example was deemed 99 to 100 percent human-written. Presumably, the site uses AI to detect AI output. Do I detect a robot conspiracy?

And so, from now on, at least as long as the good times last, our stories will come ex machina in one way or another. It’s fun, easy, and inexpensive too, but as we don’t know where all this may lead, you might want to get hold of a typewriter while they still can be had and practice your penmanship, just in case we all lose touch.

Coda

ChatGPT opened its portal in November 2022 and by February had garnered over 30 million users, more explosively than any other app to date. Within weeks, AI text generators from Google, Microsoft, Snapchat, and other Internet players, based on various language and learning models, rushed onto the field. Given our addiction to innovation, they will change everything and further distance people from one another, I fear.

Writers wanting to defend themselves might check out charcter.ai, which generates human personae based on real bios or descriptions of fictional characters users provide. These ephemeral entities can interact with one another, opening frightening possibilities for online games and literary works. Doubtless, they can and will be used to train one another to improve their credibility, and before long AI-written novels may open a new publishing niche. Be prepared.

All this automated impersonation will puzzle those alien archeologists even more about who we were. It sure puzzles me.

Geoff Dutton

[June 21, 2018, updated August 28, 2018 and March 10, 2029]

2 comments

I enjoyed your essay very much, Geoffrey. It’s mind boggling to realize that Vernor Vinge’s 1993 prediction of the point of singularity occurring in twenty to thirty years is right on schedule. I’m looking forward to reading more of your work.

Thank you Stephen for your kind words. That “singularity” that tech nerds predict can’t happen without willful human action to make it happen. It isn’t inevitable. I am truly puzzled why the barons of technology seem so eager to render themselves redundant. What is so wonderful about the prospect of draining humanity of agency to build its future? Why are we being force-fed capitalists’ version of progress? Isn’t this a democracy in which we’re supposed to have a say in our future?

If you like, please feel free to peruse my stuff at perfidy.press and my best wishes. Can you provide a reference to Vinge, whom I never encountered?