In his previous craft essay, “Tell Me a Fractal,” Geoffrey Dutton reviewed Jane Alison’s book Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative (Catapult, 2018) and speculated about how its ideas might inform a novel he was having trouble starting. He has since completed that novel, Her Own Devices, a sequel to his thriller Turkey Shoot (Perfidy Press, 2018). This essay considers ways in which some geometric forms Alison discussed found their way into Her Own Devices, consciously or not. As you write, think about what narrative patterns might enhance your story, and when you read it, look for repeating motifs, rhythms, and spatial metaphors.

When Catapult Press published Jane Alison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative in 2018, I felt it could inspire me and promptly devoured it as fodder for my second novel. A few months earlier, I had published my first one, an alt-conspiracy thriller whose tragic ending left the two main protagonists in limbo. For pious Iraqi renegade Mahmoud, limbo was just that; he died but only got part way to Paradise. For his Swiss lover and comrade Katrina, limbo was immeasurable sorrow, guilt for precipitating his demise, and a suspicion she was carrying his child. Anyone who finished Turkey Shoot had to be sad for them.

Ever after forcing myself to write that dismal denouement, I was dogged by remorse over what I’d done to them. I knew I had to make things right for my characters in another book, but I had only vague ideas about what it should be. Reading Meander, Spiral, Explode helped me to escape my creative limbo and feel my way forward. So, I started the story with my heroine giving birth and winged it, hoping that Alison’s aesthetics would ease my labor pains. I left Mahmoud to soliloquize from limbo and propelled Katrina (having reclaimed her given name, Anna) into motherhood and an adventure as an amateur sleuth without a clue of how I would script her into action.

In retrospect, I realized that Turkey Shoot exhibited at least one of Alison’s patterns, wavelets. Throughout the story, action ebbed and flowed between tense and tranquil scenes. The new book might share that pattern, but why stop there? One pattern in Meander, fractals, particularly seized my imagination. I had applied fractal geometry to cartography in my academic days1, but what would fractal prose look like, and was I up to that?

Well, here’s a simple literary fractal: naming a part or an aspect of something to denote the whole, such as “wheels” for a vehicle, “Washington” for the Federal Government, or “suits” for businessmen. It’s called a synecdoche (from Gr. “Take up together”) and it’s fractal in that the unnamed large concept hosts details that imply it. (Or as one definition of fractals says: similar patterns recur at progressively smaller scales.)

Somewhere in the third draft I renamed my new novel Her Own Devices2 (originally it was Recapitulation, speaking of patterns). The word Devices3 is a double-entendre synecdoche that refers both to the technologies my protagonist deploys (a website, email, phones, computers, surveillance devices), and to her self-presentation (codependence, self-effacement, bravado, sharing or hiding information, acting naïve) as she gathers evidence and seeks allies. And in the same sense that a synecdoche is an example of a rhetorical device, each of these things and traits exemplifies a technological or behavioral device.

Despite echoing events from its prequel, the book that emerged can’t be called a thriller. Its genre is hard to pin down. Touching all the bases, I call it “contemporary women’s literary crime fiction with magical elements.” But, aside from that synecdoche, does the story’s architecture qualify as fractal?

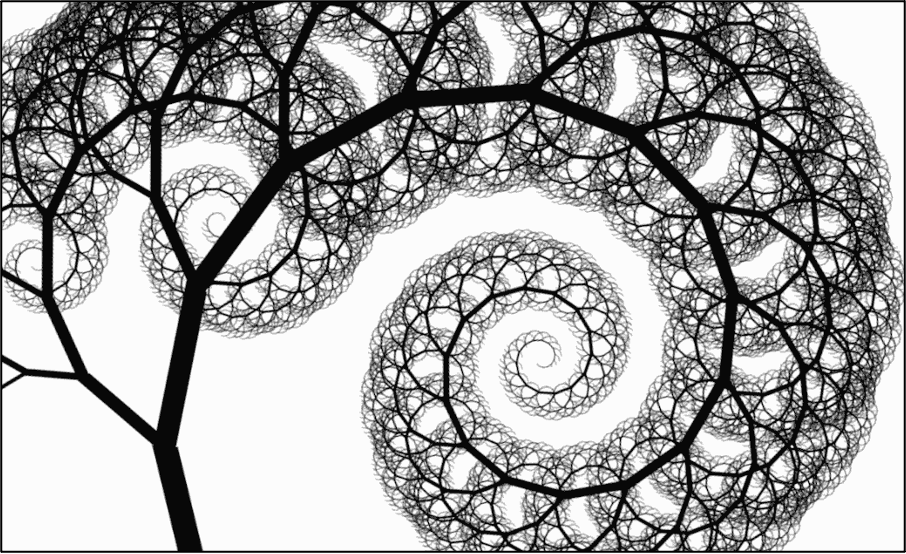

When you look at a mathematical fractal, you see self-similarity; not only do different parts of the figure look almost alike, it looks the same as you zoom in and out of it, its form governed by the parameters of the iterative algorithm that generates it. Can narratives similarly iterate by filling time rather than space, recapitulating condensed or expanded versions of events and examples of themes?

That was my intention, but I knew my task wasn’t as straightforward as coding a fractal. There’s no algorithm for fractalizing prose. Even if there somehow were, a fully fractal novel would be rather tedious to write and probably to read. But works of prose can have fractal qualities, almost inescapably so. In life, after all, people fractally inhabit rectilinear spaces inside rectilinear dwellings within rectilinear blocks inside rectilinear neighborhoods in rectilinear cities. In stories about them, we tend to expect characters to conduct themselves consistently in different locales and situations and get confused when they don’t behave self-similarly, unless they exhibit multiple personalities or are pulling a fast one.

As an example, in Her Own Devices you see self-similar behavior in Ramadi, Anna’s precocious preschool son, whose fascination with flight has many facets. You see it when you first meet him, pretending to be an airplane on a windswept street. His favorite video is Jay-Jay the Jet Plane. He chases pigeons, builds a Lego space shuttle and straps it to his backpack, covets a model plane, and in a nightmare is carried off by a bird of prey. For his next appearance I’m thinking of giving him a drone.

You might call these junior airman moments a motif4 rather than a fractal, and that’s fine. Motifs are repetitions that generally reinforce a theme and come in many flavors, some seemingly fractal, others apparently not. Ramadi’s behavior keeps an even keel; thankfully, even being exposed to child predators doesn’t color his innocent perception of the world as it might for an older child. Though his competence does increase, he maintains a constant beat.

Anna also develops competence, though her self-confidence lags behind. Her insecurities, obstinacy, and recurring doubts about her iffy project (to capture child predators) cause her to sputter along and at times play out in dialogs with her nagging inner voice whom she dubs “gizzard-brain.” As much as Anna resents its snide asides, she seems to gain some therapeutic insights, and once she recognizes it for what it is (metafictional author intrusion), Anna tells it to have a nice day.

It takes a while, but Anna does rise to the occasion. As she struggles to apply herself, her narrative thread unknowingly braids with Mahmoud’s quest for redemption. But a durable braid needs at least three strands, and in this case the third one is their shared backstory; both recount it in snippets, each describing how they met, fell in love, and became comrades in a fraught adventure that didn’t go well. Although Alison’s book doesn’t mention them, braids are formed by two or more twining strands, which she might describe as intersecting meanders. “A meander” she says, “begins at one point and moves toward a final one, but with digressive loops.” Meandering narratives, too, can plait together. In some cases, their story lines merge. In others, as here, they remain distinct; Anna’s and Mahmoud’s repeatedly intersect, but in the end they go their separate ways.

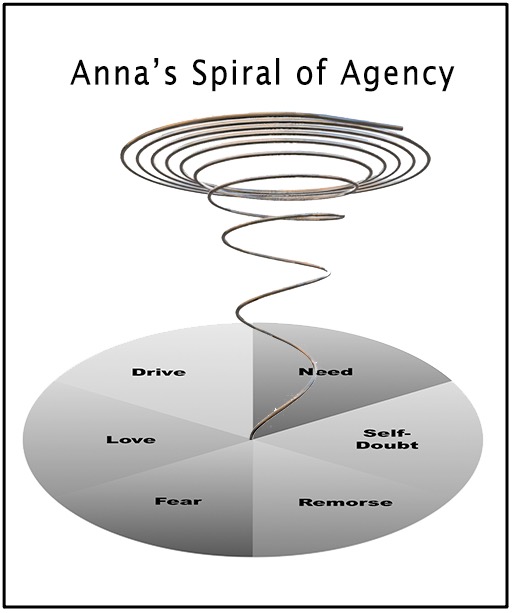

Now consider those braiding arcs as spirals, another of Alison’s patterns. Spiraling stories, she says, wind around their origin, revisiting people, places, and events as they gyre wider. Plot and character developments can spiral out, circling to revisit events and themes as they unfold. As they brush together, both Anna’s and Mahmoud’s perspectives broaden as their narrative arcs follow a parallel course to destinies on different planes.

A swirling pattern, as Alison points out, when lifted into the third dimension creates a helix, like DNA, or a vortex, like a whirlpool. Anna’s innerspring winds her arc around an origin, cycling through the same issues: need for community, self-doubt, remorse over Mahmoud’s death, fear of retribution, and a difficult love interest. She’d be stuck in a vicious cycle were it not for her drive. Revulsion over child trafficking becomes an obsession to see justice done, overcoming, and in some ways leveraging the traits that have been holding her back.

Anna emerges from a disconsolate fog of wistfulness and worry to build a network of homeschooling moms that becomes the core of a movement to stamp out child trafficking. She goes online with it, creating a social network she recasts as a telephone tree (a radially branching structure Alison would label an explosion). It fans out organically, ultimately connecting her to people she’s never met, some of whom rally to her aid. (Thus the book’s motto: “You never really know who your friends are until you need them, and even then you might not know, but that’s okay.”)

Meanwhile, stranded in a featureless limbo, Mahmoud’s spirit slowly constructs a metaverse of places he visited in life, in Greece and back in his homeland; the rest of the world is shrouded in mist. Visiting his aunt’s house in Iraq, he gathers that his only brother survived his abduction by Daesh (Isis) and has fled from Syria to Athens, where he drives a gypsy cab. Like Anna, Mahmoud goes on a quest — to connect her and his brother Akhmed — but without agency it’s a mission impossible. He shadows Anna trying to sense her state of mind and what she’s up to. As their narratives spiral in a double helix, his fog, too, begins to lift. Eventually, Mahmoud finds his brother, who ends up taxiing him, Anna, Ramadi, and three others — all oblivious to Mahmoud — to rescue a child.

Each of these characters has a unique voice, sometimes directed at the reader. Mahmoud’s always is, along with the narrator’s. Anna’s is in her Foreword and Afterword. Gizzard-brain’s is directed at Anna from the writer. Juxtaposing multiple voices like this could be confusing.

Most novels are written in one voice (typically an identified or anonymous narrator), and in one person (typically third, but first-person narrators are not uncommon). “Omniscient” narrators are almost always voiced in the third person. But there are other choices, other voices.

Some novels employ several narrators. Renée Knight’s Disclaimer, which I reviewed in these pages last March in connection with Her Own Devices, has two that alternate between third-person omniscient and first-person limited. Because each has its own chapters, it is easy to perceive the current point of view. In Devices, however, voices commingle.

Inviting in more than two or three narrative voices can confuse readers about who’s talking and what they know. Testing the limits of narration, Devices speaks in six voices: principle protagonist Anna, her inner voice, Mahmoud, the editor, the writer, and the narrator. The writer (my voice) speaks indirectly to readers via his fictional editor, coming off as a journalist who happens to be psychic, and via Anna’s inner critic.

A novel with six voices isn’t as cacophonous as it may sound. The narrator carries most of the weight. Anna only speaks directly to readers in the Foreword and Afterword, in conversation with the editor. Her and Mahmoud’s diction and typeface distinguish their narratives. Typefaces also signify text messages, emails, and Anna’s inner critic.

All these fictional and metafictional points of view mingle and coil, but that should not confuse. Besides the reader, each addresses a particular audience. In order of appearance:

- Writer → Narrator; Editor (by implication); Anna (via inner voice)

- Anna → Editor; Inner voice; Characters

- Inner Voice → Anna

- Editor → Anna; Writer (by implication)

- Mahmoud →Characters (who can’t hear him)

- Narrator → Only the reader

Other characters speak, of course, but only to one another. Being privy to all these voices gives readers more omniscience than the narrator, who, once he takes over, has no need to hop heads but occasionally drills into Anna’s.

The voices listed above debut and then recur in a symmetrical recursive5 sequence: First, the writer introduces himself. Anna voices the Foreword, bewildered, harassed by her inner voice (the writer as ventriloquist), to skeptically interrogate the book’s editor. Part One follows, introduced by Mahmoud (as he does the three subsequent parts6). The narrator then voices 31 chapters, occasionally interrupted by Anna’s critic and by Mahmoud, who also provides closure at the end. Then it’s back to Anna in the Afterword, before finishing with the writer’s bio. 1-2-3-4-5-6-5-4-3-2-1: the circle of voices is unbroken.7

Fictional, metafictional, and metaphysical elements mingle and coil within this narrative structure, encapsulating the story’s DNA, as son Ramadi physically encapsulates theirs. Metafictional elements are limited to front and end matter and Anna’s inner voice. Mahmoud is an ongoing metaphysical presence that no character apprehends, yet his and Anna’s arcs are twining spirals, a double helix that I’m thinking might have metaphorical issue in a following book.

And this manipulative writer who speaks in tongues, whose voice is that? Well, my name is on the cover, but suppose it was ghostwritten? Let’s not go there. There’s only so much a reader needs to know.

Jane Alison made me want to tell a fractal. Maybe I did, maybe I didn’t, but I’m sure reading Meander, Spiral Explode influenced my prose. It just wasn’t obvious at the time. Literary analogs to geometric forms can be hard to spot unless you know what you’re looking for; so give her book a read, and then reread one of your favorite novels to tease out patterns. And if you’re a writer, maybe thinking that way will help you shape your craft.

1GH Dutton, Fractal enhancement of cartographic line detail, The American Cartographer, 1981

2The premise of the novel is described here. Find excerpts from it at The Write Launch.

3“Device” stems from “devise,” which in Middle English meant “desire” or “intention.”

4A motif (from French for “pattern”) is a recurrent symbolic image, phrase, or idea. Motifs can be symbols, sounds, actions, ideas, or words. Motifs strengthen a story by adding images and ideas to the theme or themes that give meaning to the narrative.

5A recursive algorithm repeatedly calls itself, perhaps with changing parameters, and when it’s reached some limit, unwinds and returns control to whatever code called it.

6For this recursive structure to be more fully fractal, each of the four themed parts’ eight chapters could be divided into four chapters, each set with a different theme, and then divided one more time into sets of two. I never even considered attempting to do that.

7Jane Alison points out that David Mitchell’s novel The Cloud Atlas exhibits this same circular symmetry, with five different opening chapters, a complete middle chapter, and then five closing chapters, each completing their opposite number’s story. She finds that pattern somewhat fractal, as she might my cycle of voices.